Essential Shoulder Mobility Tests for All Climbers

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 92

INTRODUCTION

Having good, symmetrical shoulder mobility can reduce injury risk while enhancing climbing performance. It’s pretty easy to understand why being super limited, or hypo-mobile, in your shoulders is a problem for climbers.

What many people don’t consider, however, is that it’s equally important to not have too much shoulder mobility, or hyper-mobility.

It’s a common misconception to think “the more mobility, the better!” But in fact, if you’re hypermobile, stretching is exactly what you don’t want to do.

So how are you supposed to know if your shoulders have too much, too little, or just the right amount of mobility? And what do you do about it once you find out?

Well, in this video I’m going to show you two tests that will help you determine your mobility, as well as my recommendations at the end. And yes, you need to do both tests you want an accurate result ;).

TEST 1 - Functional Shoulder Test

The first is a Functional Shoulder test. This involves functional movement patterns that require good shoulder, scapula, AND thoracic spine mobility.

Don't push this test or your mobility to the point of pain. It should be relatively comfortable. If you do immediate pain while attempting this test, you may have a separate shoulder pathology that may require a skilled professional to diagnose and treat.

To perform the functional shoulder test

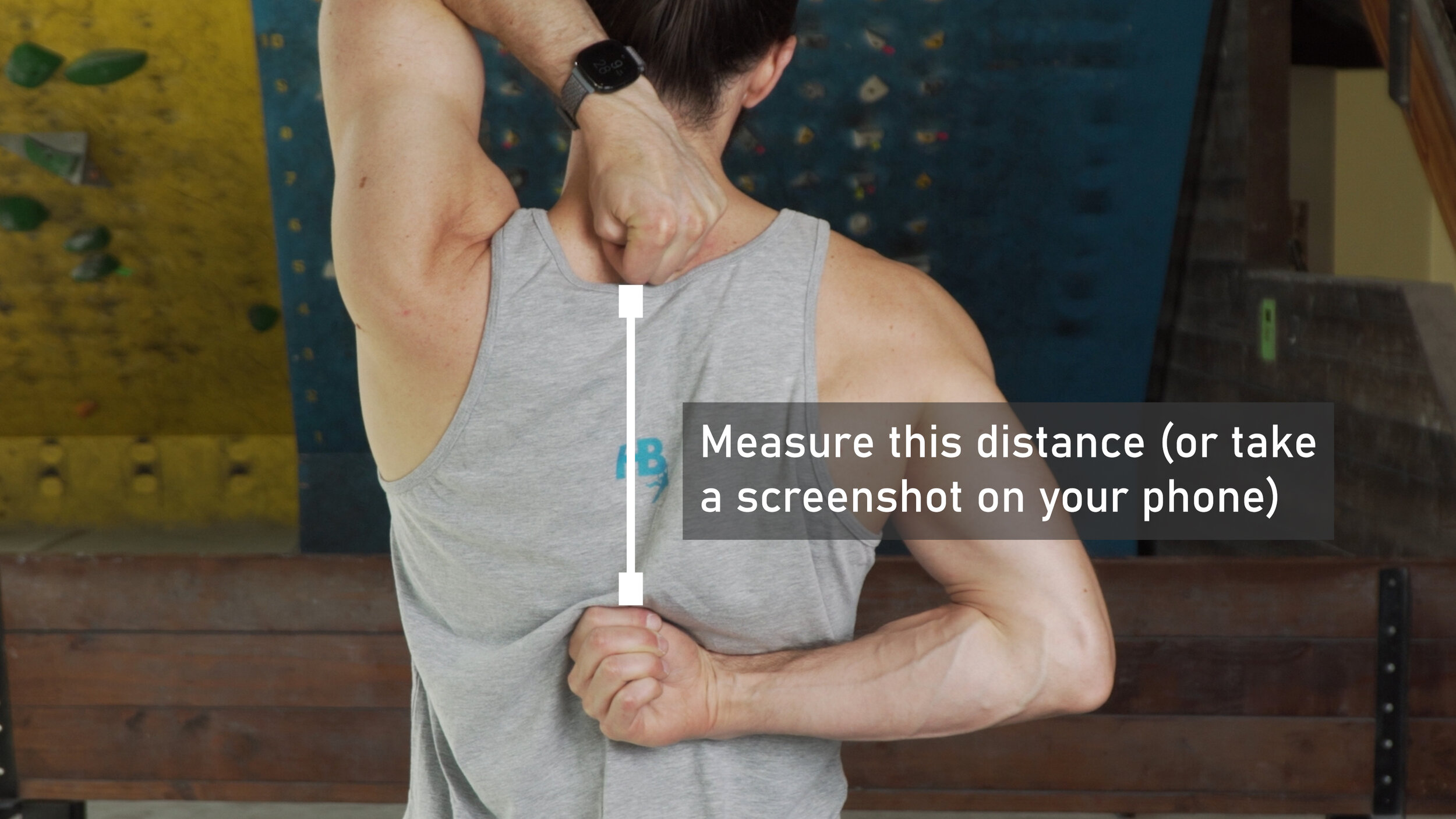

Grab a friend, or use your phone to record your test.

If using a friend, you’ll also need a tape measure or ruler.

If using a phone, it should be set up looking at your back and needs a clear shot of your mid back region.

Make a fist with both hands, tucking your thumb inside the fist.

Place one of your arms behind your back and work your fist up as high as you can along your spine.

Reach your opposite arm behind your head and work it down as far as you can along your spine.

Have your friend measure the distance between your two closed fists.

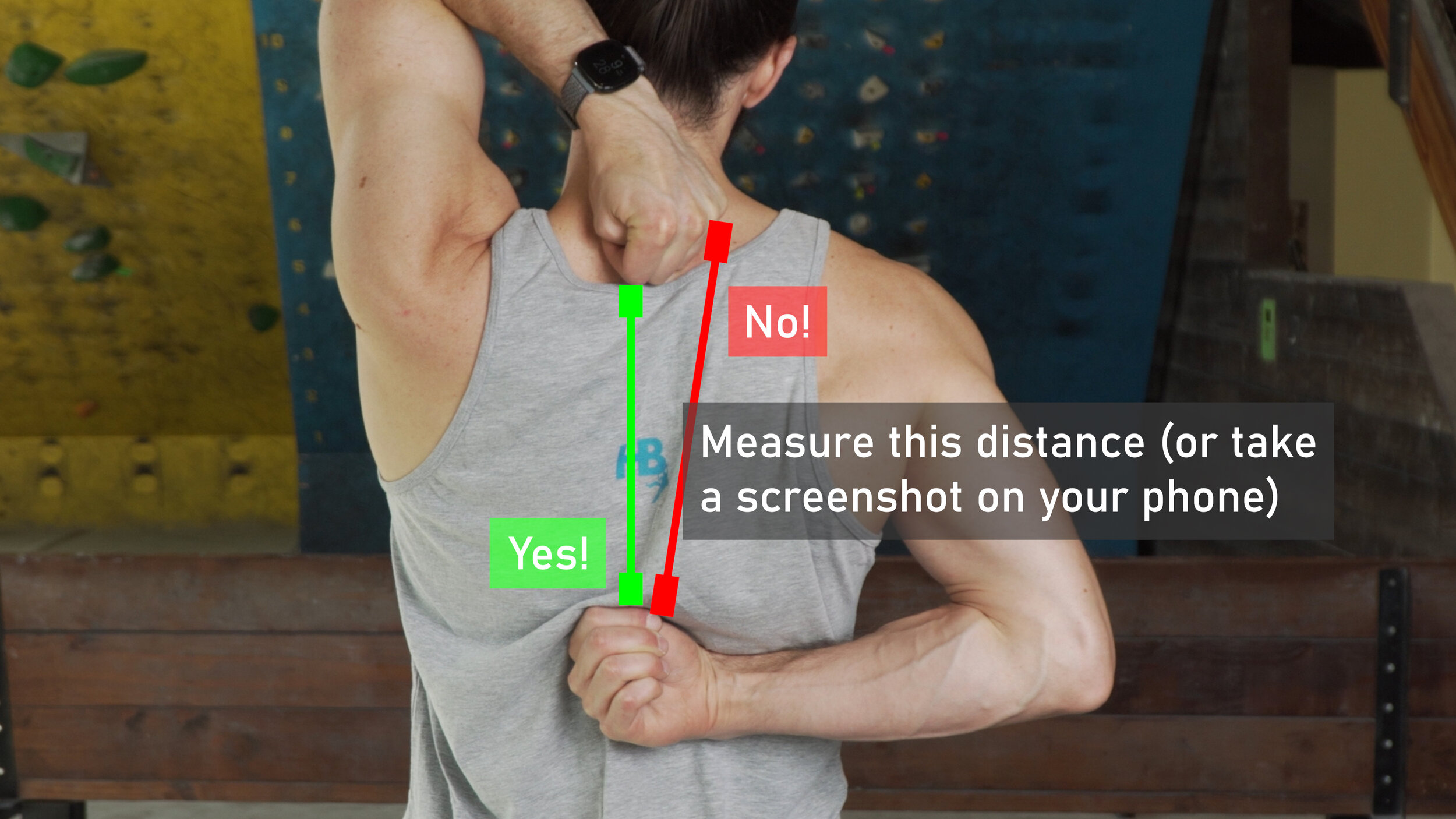

Measurements should be made from the closest bony prominence.

Repeat, but switch arms!

This test can be repeated up to 3 times per side to increase accuracy

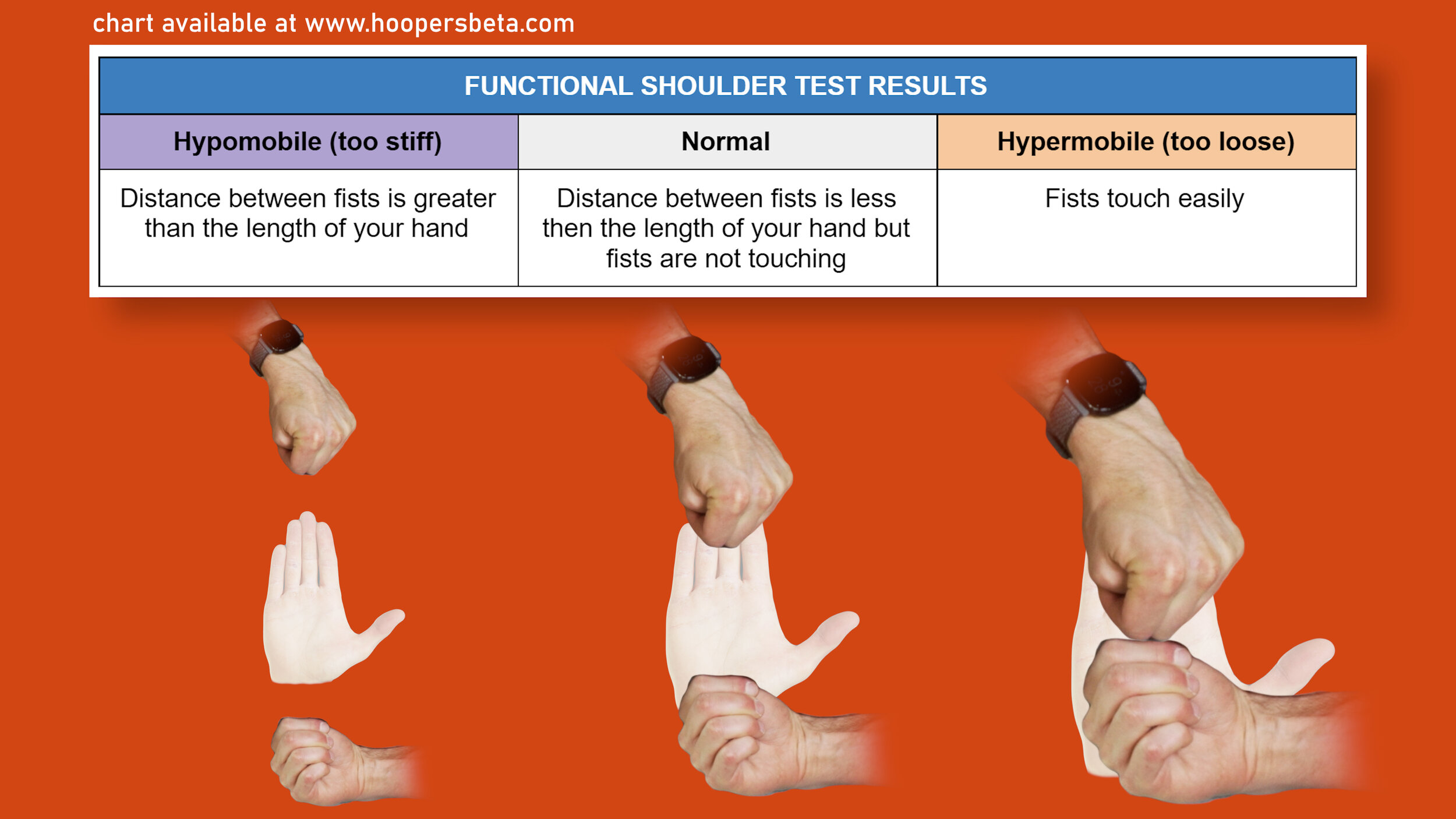

Now for the results. Take the measurement that your friend found and compare that to the length of your hand (from the base of your wrist to the tip of your middle finger).

If the measurement turns out to be equal to or slightly shorter than the length of your hand, you have normal mobility!

If your measurement was longer than the length of your hand, then you have a small deficit in your range of motion.

If you were touching hands together, you may have hypermobility in your shoulders.

For a super simplified version of this test, just see if you can touch your fingers together. If so, you probably have normal mobility. If not, you might be slightly limited. If you can go way past your fingertips, you might be hypermobile. Just keep in mind that doing the test this way is not how the test is done or how it is researched, so it will not be as scientifically accurate

TEST 2 - “GIRD” Test

The second is the “GIRD” test, which stands for “Glenohumeral (shoulder) Internal Rotation Deficiency.” This test is used to specifically measure the internal and external rotation of the shoulder.

To perform the GIRD test

Grab a pencil, piece of chalk, or anything that you can use to write on a wall

Grip it so the tip is pointing out on the side of your pinky

Bend your elbow and place it on the wall with your arm directly out to the side (90 degrees)

Your body should be perpendicular to the wall and the forearm parallel to the ground

Draw an arc with the pen, forward and backward, while keeping your elbow in the same place and not moving your chest.

Try to avoid compensations, such as movement in the chest or excessive movement of the shoulder blade. Be true to your measurement. This will increase your accuracy.

Using a goniometer or protractor (or an app on your phone) to measure the angle of the arc.

Repeat on your other arm

Now for the results. Normal, scientific values for shoulder internal and external range of motion will vary based on what source you look at, your age, and the frequency and intensity of your climbing. Since there are so many variables, we’re going to show you what the science says is normal as well as what’s more realistic for climbers based on a little expert opinion and math.

For external rotation, the normal scientific range is 80-90 degrees with an average of 83 degrees. However, climbers often need a bit more external rotation to perform various moves safely. In fact, I would argue that 80 degrees is not enough for climbing. Rather, my recommendation for external rotation for climbers is 90-115 degrees.

For internal rotation, the normal scientific range varies greatly depending on the source, with one lit review finding the acceptable range to be 60-100 degrees and another finding 30-110 degrees! The average, however, is 74 degrees. But with such wide ranges and not much other sound science to stand on, we’re again going to have to rely on a bit of expert opinion and some calculations. TL;DR: my recommendation for internal rotation for climbers is 61-86 degrees

Now, there’s one last number we need to be aware of and that’s our total range of motion -- our external rotation value plus our internal rotation value. Wilke et al shows that a total value greater than 176 degrees may increase injury risk. So, once you’ve calculated your individual ranges of motion, add them together. If the total is more than 176 degrees, you may be hypermobile.

To use science to figure out our appropriate internal range of motion values, let’s start with some research. Wilke et al, showed that having >176 degrees of TOTAL motion (internal + external rotation) may increase injury risk. We also know that normal ROM for external rotation is 80-90 degrees. So, if you have 80 degrees of external rotation you don’t want to exceed 96 degrees of internal. If you have 90 degrees of external, you don’t want to exceed 86 degrees of internal. So the theoretical max would be 86-96 degrees of internal. We also have two sources that show a minimum of 30-60 is normal, so we’ll leave the minimum range of internal to be 30-60 degrees.

Research shows that the normal for external rotation is 80-90 degrees and considers the hypermobility factor to exceed 115. So, if you have the max of 115 degrees of external rotation, then you should not exceed 61 degrees of internal rotation.

If you have a minimum norm of 80 degrees of external rotation, then you should not exceed 96 degrees.

We also have the two research value minimums of between 30-60 degrees, so we can use that range as our scientific minimum.

But, let’s make this more appropriate for climbing since I think a more appropriate range would be 90-115 degrees of external rotation. Using 176 again for our total motion (internal + external) leads us with the following: if you have 90 degrees external then you max would be 86 internal. If you have 115 of external then 61 would be your max internal. So, we can say that our ideal range could be between 61 and 86 degrees of internal rotation, which, wouldn’t ya know it… works out perfectly well since the average for internal is 74 degrees! AND the average of 61 and 86 is… *drum roll* 73.5 degrees!!! How perfect, right?

So my recommendation would be 90-115 of external, and between 61 and 86 of internal, as long as your total range does not exceed 176 degrees.

Now that you know your shoulder mobility, what do you do about it? Here are my recommendations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

If it turns out that you are hypermobile in both tests, you’ll definitely want to focus on strengthening the shoulders rather than further increasing mobility. Check out our video “Top 6 Exercises for Rotator Cuffs” for some great examples. Or, for a follow along check out our video “Killer Home Shoulder Circuit for Rock Climbers”

If it turns out you were hypomobile or stiff with both tests, then you’ll definitely want to address those tight areas with specific stretches! In that case, we have you covered once again. We’ll be coming out with a video on improving shoulder mobility, so keep an eye out for that and we’ll put a link in the description when it’s live.

If in the special case you were hypermobile with one test and hypomobile with the other, pay attention to the small details. What areas did you feel tight in? Where were you too mobile? You may need to do some more self assessment and see where you feel strong vs where you feel weak. In this unique scenario, you may want to check out both our shoulder strengthening videos and the upcoming video on shoulder mobility. As you go through the routines, pay attention to what is particularly challenging to you and what feels easy and focus on the challenging aspects. Or, if you still feel lost, definitely reach out to a skilled provider who can assist you further.

OUTRO

For our final note of the day, let’s remember: Being hypomobile doesn’t GUARANTEE an injury. Just like being hypermobile doesn’t either. The studies and science I used for this video highlight an increased risk one way or another, but they do not lay out an absolute determination.

Mainly, it’s important to understand that if you’re strong but lacking mobility, that’s a deficit. If you’re super mobile but weak, that’s also a deficit. It’s essential for climbers to address obvious deficits to make sure we can be strong and healthy and not suffer an injury that takes away time from climbing.

And that’s it for today! Train those shoulders to perfection, whether that means adding mobility or stability. Climb your buddy’s project having unlocked secret beta that they could only dream of. Send it while watching them try to subdue their violent jealousy with their stoke for you. Repeat! Just to really show them the appropriate beta. You know, because your friends!

Disclaimer

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Produced by Jason Hooper (PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS) and Emile Modesitt

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

RESEARCH

Title

The relationship between glenohumeral joint total rotational range of motion and the functional movement screen

Citation

Sprague PA, Monique Mokha G, Gatens DR, Rodriguez R Jr. The relationship between glenohumeral joint total rotational range of motion and the functional movement screen™ shoulder mobility test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(5):657-664.

Key Takeaways

Wilk14 found that 78% of all injuries documented in their study exhibited a TRROM > 176. They hypothesized that too much mobility of the glenohumeral joint may place excessive demands on the dynamic and static stabilizers of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints.

The FMS shoulder mobility test should not be used alone as a means of identifying clinically meaningful differences of shoulder mobility in the overhead athlete. Clinicians working with overhead athletes may consider using both assessments as a complete screening tool for injury prevention measures.

Burkhart and Morgan9 reported a significant loss of internal rotation in symptomatic throwing shoulders of 124 baseball pitchers with type II SLAP lesions confirmed by arthroscopy.

Relatively small differences (>5) in dominant versus non-dominant GH rotational range of motion have been suggested to be clinically relevant and have been shown to result in a greater likelihood of injury.

The subject’s hand length is measured from the joint line of the wrist to the tip of the third digit

The subject is then asked to reach one arm overhead and down their thoracic region while reaching the contralateral upper extremity behind and up their back, attempting to place their hands, closed in fists, as close together as possible. A distance between hands in this position less than the measured hand length is considered a score of “3”. A distance between one hand length and one and one-half hand lengths is considered a score of “2”, and a distance greater than one and one-half hand lengths is given a score of “1”.

If pain is felt during the test, a score of zero is given.

Wilk14 found that 78% of all injuries documented in their study exhibited a TRROM > 176. They hypothesized that too much mobility of the glenohumeral joint may place excessive demands on the dynamic and static stabilizers of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints.

The current study investigated the relationship between GH joint TRROM and a functional shoulder mobility test within a movement screen that has demonstrated validity in injury prediction in athletic populations

The FMS shoulder mobility test considers these multiple contributors to normal movement and allows for a quick screen of the region to identify potential impairments that may lead to musculoskeletal injury.

Contributors to dysfunction during the FMS shoulder mobility test may include thoracic extension mobility limitations, scapular mobility or stability limitations, and GH joint stability or mobility impairments.

If the thoracic spine lacks the ability to extend, then the behind back reach internal rotation pattern can be limited. Lack of scapular mobility from tissue extensibility dysfunctions can also contribute to a lack of normal shoulder girdle movement that has been associated with injury.,7,9,38 Rotator cuff insufficiency has been shown to alter glenohumeral joint translation during active movements which can contribute to mobility deficits

Identifying causes of asymmetry found during movement screening may assist in the correction of functional movement and aid in injury prevention measures.

Title

Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Risk of Upper Extremity Injury in Overhead Athletes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review

Citation

Keller RA, De Giacomo AF, Neumann JA, Limpisvasti O, Tibone JE. Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Risk of Upper Extremity Injury in Overhead Athletes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Sports Health. 2018 Mar/Apr;10(2):125-132. doi: 10.1177/1941738118756577. Epub 2018 Jan 30. PMID: 29381423; PMCID: PMC5857737.

Key Takeaways

Shoulders with GIRD favored an upper extremity injury, with a mean difference of 3.11°

Shoulder total range of motion suggested increased motion (mean difference, 2.97°) correlated with no injury (P = 0.11), and less total motion (mean difference, 1.95°) favored injury (P = 0.14). External rotational gain also favored injury, with a mean difference of 1.93

The pooled results of this systematic review and meta-analysis did not reach statistical significance for any shoulder motion measurement and its correlation to shoulder or elbow injury. Results, though not reaching significance, favored injury in overhead athletes with GIRD, as well as rotational loss and external rotational gain.

In 2011, Wilk et defined GIRD as a 20° or greater loss of IR in the throwing shoulder compared with the nonthrowing shoulder.

After review and synthesis of data from 17 publications, findings, though not significant, suggest that GIRD may be a deleterious adaptation to the shoulder. Evidence also suggests an increased TROM may have a protective effect from injury, while loss of TROM may be detrimental to the overhead athlete.

The results from our analysis help to corroborate the aforementioned results, with TROM deficit showing a nonsignificant association with risk of injury; the data also support the reverse, that those players with increased TROM on their dominant extremity may be protected from injury.

Title

Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Citation

Johnson JE, Fullmer JA, Nielsen CM, Johnson JK, Moorman CT 3rd. Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 May 22;6(5):2325967118773322. doi: 10.1177/2325967118773322. PMID: 29845083; PMCID: PMC5967160.

Title

Normal range of motion of the shoulder: an imprecise benchmark

Citation

Normal range of motion of the shoulder: an imprecise benchmark

Anderton M, Ede M Newton, and Holt E

Orthopaedic Proceedings 2012 94-B:SUPP_XXXIX, 127-127

Key Takeaways

The literature review confirmed there to be a wide variation in the normal shoulder ROM. The published average and range values for specific shoulder movements were: forward flexion 165 (117–180), extension 54 (28–80), abduction 171 (117–189), internal rotation 74 (30–110), external rotation 83 (40–117).

Title

Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in throwing athletes: current perspectives.

Citation

Rose MB, Noonan T. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in throwing athletes: current perspectives. Open Access J Sports Med. 2018;9:69-78. Published 2018 Mar 19. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S138975

Title

A Comparison of Glenohumeral Internal and External Range of Motion and Rotation Strength in healthy and Individuals with Recurrent Anterior Instability

Citation

Sadeghifar A, Ilka S, Dashtbani H, Sahebozamani M. A Comparison of Glenohumeral Internal and External Range of Motion and Rotation Strength in healthy and Individuals with Recurrent Anterior Instability. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2014;2(3):215-219.