How Pullups Work (WIDE GRIP, STANDARD, & CHIN-UP BIOMECHANICS)

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 111

INTRODUCTION

Now I’ve never been a gamblin’ man [flips coin, catches it on back of hand], but I’d like to make you a wager: By the end of this video, you’ll know more about pull ups than any of your friends AND you’ll have a much more solid grasp of your own anatomy.

If I win, you’ve gotta leave us a nice comment to make our egos happy. If you win, well… I’ll give you a little something at the end of the video ;).

Deal? Well giddy up! This is the surprising biomechanics of pull-ups.

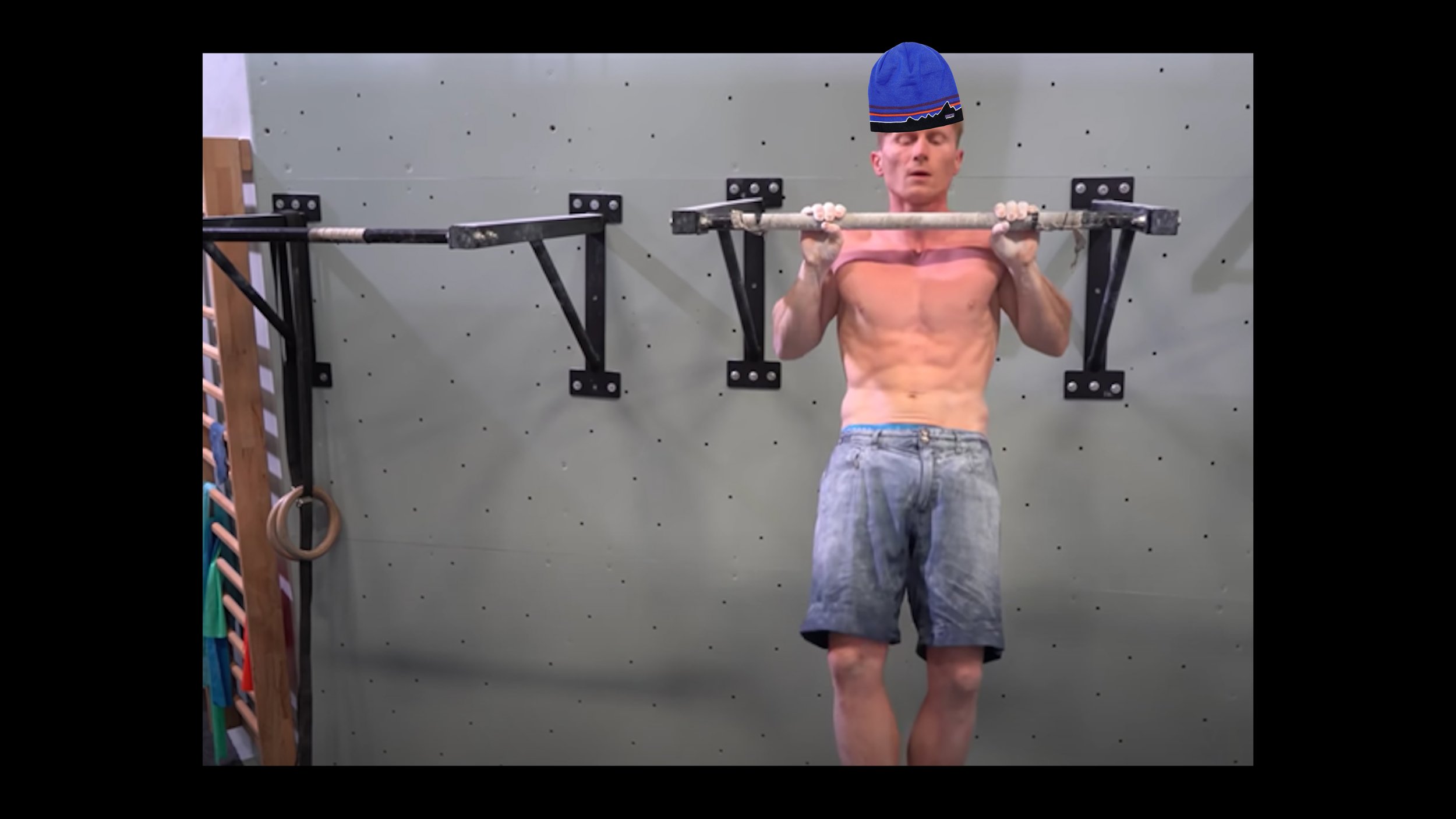

STANDARD PULL UP

Ahh, the standard grip pullup, beloved by climber bros, gym bros, crossfit bros, and Magnus Midtbros. Dating back hundreds or possibly even thousands of years, the standard pull up is a beacon of fitness for the newly initiated climber and a bastion of upper body fortitude. Due to the highly functional shoulder and hand position, it’s easy to see why this exercise is the default for every D-Woods wannabe who aspires to shirtless sends at a gym full of normies. With a wonderfully balanced distribution of force between muscle groups (if you do it correctly), the biomechanics of the standard pull-up make this one of the safest variations with a low risk of shoulder impingement. But what are the biomechanics, you ask?

Starting off with the hands slightly wider than shoulder-width, the brachialis helps kick things off by bending our elbows while the lower trap stabilizes our scapulas. The lats will of course be immediately active here too, helping pull the humerus down towards the body throughout the entire pullup. As we approach the middle range, the biceps start to engage more to keep flexing our elbows while the rhomboid major and middle trap take over for the lower trap. To avoid going straight up into the bar and concussing ourselves, we also see activation of the teres major and subscapularis, two internal rotators of the shoulder. This helps set us up to get our chest to the bar! And don’t forget the infraspinatus muscle (external rotator) that helps balance this all out!! At the end is when things take a surprising, final twist! Since the elbow is almost maximally flexed, the biceps can’t pull you up anymore, so the triceps actually turn on to get that last little chest-to-bar push.

The main risk, albeit small, with the standard pull-up comes from the load to the brachialis and biceps brachii, so if you have had issues with these regions recently, you may need to reduce this activity. Of course, if you have terrible form, you’re also going to put yourself at some level of risk. Large compensations in your shoulders and upper traps can lead to pain in those areas, or, at the very least, simply won’t engage some muscles the same way as a textbook pull-up would.

If you’re having trouble with this classic version, it’s likely due to weakness in the elbow flexors, the back muscles including the lats, or… both! I would recommend doing body weight-assisted pull-ups or lat pull-downs to help train up to it.

FREE HELP FOR CLIMBERS

Hey, if you’d like to support us on our journey to create the largest library of free training and recovery info for climbers, please like this video and consider sharing it with others.

WIDE GRIP PULL UP

So, you think you’re too good for the standard pull-up. You see Adam Ondra spanning moves across the Atlantic and you wonder how his shoulders don’t explode, so you do a little scientific research and find out about wide grip pull-ups. The superior scapular control, the shoulder stability, the big back energy… All you can think about is going wider. That is, until you try it out. Now, you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to understand why wide pull-ups are harder than standard pull-ups, but let’s ask one anyway.

[Super complicated physics explanation from Shannon here - please watch the vid for his description!]

Oh…yeah…I get it. Soooo simple. But for those of you who didn’t get that, let’s explain it a different way.

With hands now much wider than shoulder-width, the brachialis and biceps will once again help us get started. However, our shoulders and arms are now more mechanically disadvantaged here than the standard pull up, forcing us to rely more heavily on our lats to pull us up rather than elbow flexion. Our traps and rhomboids will also have to work a lot harder since our scapulas are pulled farther apart. If you have the mid back strength to get into the middle range, the rhomboid major will really join the party to continue pulling those shoulder blades close together. And just like the standard pull up, at the end of the motion the triceps will fire up to help the lats and mid back get your chest up to the bar.

The risk of this variation is related to shoulder impingement due to poor scapular stabilization. If you notice your scapulas rising, significant asymmetry between sides, or your shoulders rolling forward (protracting), these are essentially compensations creating poor mechanics in your back and shoulders and increasing your risk of injury. This risk can be mitigated by consciously practicing good mechanics (like scapular retraction), load management when introducing this into your training, and using body weight assistance as needed to ensure proper form.

If you have difficulty with a standard pull-up, you should likely get stronger with those first before moving on to the wide grip as you probably need to increase your back strength.

Once that feels easier, rather than go straight for a huge span, just slightly move your hands further out and track your progress over time.

REVERSE GRIP PULL UP (CHIN UP)

Well, well, well, you just couldn’t stay away, could you? You may have successfully gotten wide AF, but now you’re greedy. You see those other bros going huge on bicep curls, doing curls on top of their curls, and you wonder why your lowly pull ups can’t give you the same workout. But then, through sophisticated calculations, you uncover a technique that takes your pull ups to the next level: the reverse grip. Sure, the increased bicep activation could be helpful for some climbing positions, but you know you’re really doing them to get ready for: Hot Bro Summer!

Luckily, for the sake of your climbing ability, reverse grip pull ups are actually much more than simple biceps curls. They’re sort of a nice middle ground between standard pull ups and rows.

With the forearms in supination (or palms facing toward you), we’re once again kickstarted by the brachialis and eventually the biceps. Surprisingly, though, the pec major muscle is also highly active in this position! It helps counter the high external rotation of our shoulders while also likely helping to extend the humerus and pull our body up. The supraspinatus is also quite active throughout the range, working hard to stabilize the shoulder. Up through the middle range, the infraspinatus is also working as an adductor, protecting the shoulder from risky positions. As we approach the end, the deltoids also turn on to add further stability to the shoulder and help out that poor supraspinatus. The triceps showed up a bit early to the party this time too! They were trying to help extend the shoulder and then really make their presence known at the end for that final push.

The biomechanics of this pull-up make it mostly safe, but perhaps not the ideal choice for those with shoulder instability, a history of supraspinatus issues, or history of bicep issues (especially those of the long head!). This position with the extreme external rotation demands greater rotator cuff activation, so if you’re recovering from such an issue this may not be your go-to.

If you’re having difficulty with this variation, it could be due to weakness in the elbow flexors, mild instability of the shoulder, or simply just difficulty coordinating the movement with all of the various muscles involved.

WHAT ABOUT NARROW, NEUTRAL, AND ONE-ARM PULL UPS?

I know we said we were only going to talk about the three main pull-up types, but we had to throw this in as a little bonus, because other types of pull ups have their own relative strengths and weaknesses as training tools. Except for he who shall not be named.

The narrow grip is similar to the standard pull up in a lot of ways, but biases the forearms and wrist flexors even more. As climbers we don’t typically have a significant deficit of forearm strength and there are other, more specific ways of training it, but narrow pull ups can still be a nice variation to try out.

The neutral grip does have some functional advantages for crack climbers and moves like this [b-roll clip] where your hip is parallel to the wall. It obviously falls somewhere in between the standard grip and reverse grip, with some pec activation but more engagement of the brachioradialis than the long head of the bicep.

Overall, narrow and neutral grip pull ups generally aren’t quite as useful for climbers to train, but it’s always good to be aware of them to keep things fresh and varied.

As for one arm pull-ups, the biomechanics can be quite a bit different than two-arm pull-ups. If you'd like us to make a video on that, let us know in the comments!

OUTRO

Well, who won the bet? If it’s me, you know what you gotta do. If it’s you, shoot… a deal’s a deal. Here’s a coupon code for 15% off anything in our store. I am a businessman after all ;).

Until next time…

Train the appropriate pull up position that will help you climb the project you were struggling with so you can send it with ease. And once you stick the final jug, hang around with your great shoulder stability, do a pull up, aaaaand repeat.

CITATIONS

Urbanczyk CA, Prinold JAI, Reilly P, Bull AMJ. Avoiding high-risk rotator cuff loading: Muscle force during three pull-up techniques. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30(11):2205-2214. doi:10.1111/sms.13780

Dickie JA, Faulkner JA, Barnes MJ, Lark SD. Electromyographic analysis of muscle activation during pull-up variations. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2017;32:30-36. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2016.11.004 [2]

Youdas JW, Amundson CL, Cicero KS, Hahn JJ, Harezlak DT, Hollman JH. Surface electromyographic activation patterns and elbow joint motion during a pull-up, chin-up, or perfect-pullup™ rotational exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(12):3404-3414. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f1598c [3]

Prinold JA, Bull AM. Scapula kinematics of pull-up techniques: Avoiding impingement risk with training changes. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(8):629-635. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.08.002 [4]

Leslie, Kelly & Comfort, Paul. (2013). The Effect of Grip Width and Hand Orientation on Muscle Activity During Pull-ups and the Lat Pull-down. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 35. 75-78. 10.1519/SSC.0b013e318282120e. [5]

Disclaimer

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com