How to Fix Lateral Knee Pain for Climbers (Outer Knee Pain, LCL Pain)

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 104

INTRODUCTION

No matter what’s causing your lateral or “outer” knee pain, it is treatable! So in this video we’ll discuss why lateral knee pain happens in climbers, how to diagnose your specific issue, and what you can do on your own to fix it. Let’s goooo!

CAUSES OF LATERAL KNEE PAIN

Lateral knee pain from climbing-related activities is common due to the high stresses we impose on our legs while heel hooking, high stepping, hiking, and of course falling.

These activities can result in traumatic or overuse-related injuries to one or more of the following tissues:

The biceps femoris

The iliotibial band or ITB

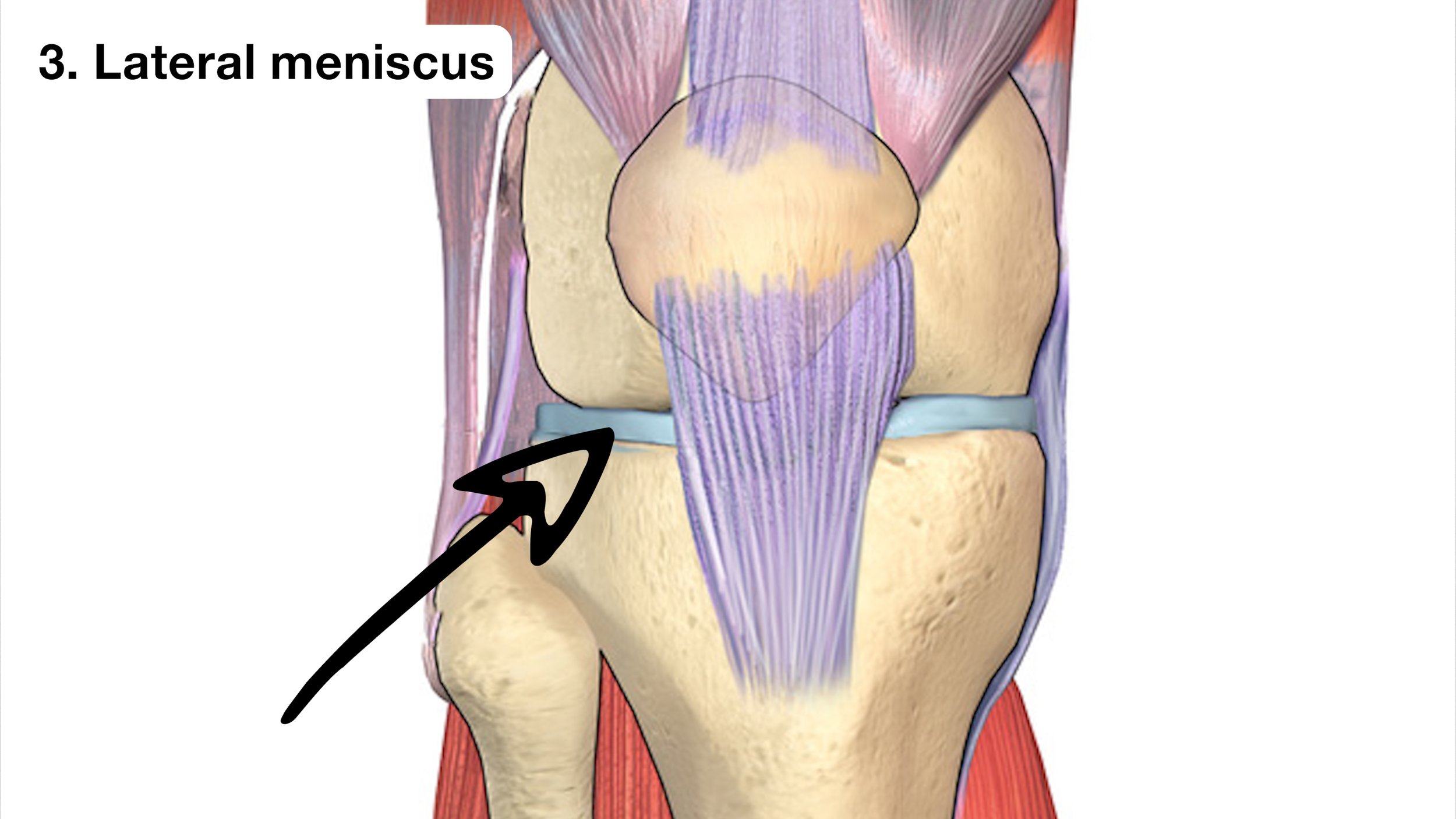

The lateral meniscus

The lateral collateral ligament or LCL

Biceps Femoris

The biceps femoris is one of our hamstring muscles. The tendon for this muscle attaches on the back, lateral side of our knees. That tendon can get damaged if loaded with excessive force, which can easily happen during a heel hook. This maneuver often places rotary forces on the knee as well, which can exacerbate the strain on the biceps femoris and other hamstring muscles.

ITB

The ITB is a dense piece of connective tissue that runs along the outside of our knees. It typically causes lateral knee pain due to contact with the lateral condyle of the femur. While heel hooking, the ITB is fully tightened and can press up against that condyle. If there is a subsequent overload of force in that position, like when your foot slips or you miss a hold, the ITB can get sprained. Alternatively, ITB issues happen from hiking due to suboptimal biomechanics of the lower extremity or poor form while walking. Lack of glute muscle engagement and frequent knee valgus (knee moving inward) increases rubbing of the ITB on the femur, resulting in irritation.

Lateral Meniscus

The lateral meniscus is a disc-shaped chunk of fibrocartilage that acts like a “shock absorber” in the knee. It can tear as a result of trauma to the joint and is particularly vulnerable during twisting or rotating of the knee as well as when the knee is fully bent. Gnarly heel hooks, off-balance high-steps, and uneven hiking terrain can expose the meniscus to these types of forces.

LCL

Finally, the LCL is a ligament on the outer side of our knees. It can be sprained or torn from traumatic force to the knee, however, it is less likely to be injured during climbing-related activities than the other three tissues. This is because climbing usually does not create enough varus force on the knee (bowing the knees out) to cause injury to the LCL. Yes, heel hooking does create this effect, but typically the force will be higher on other structures and those are more likely to injury before the LCL So, if a climber does suffer an LCL injury, it would most likely be due to a traumatic fall.

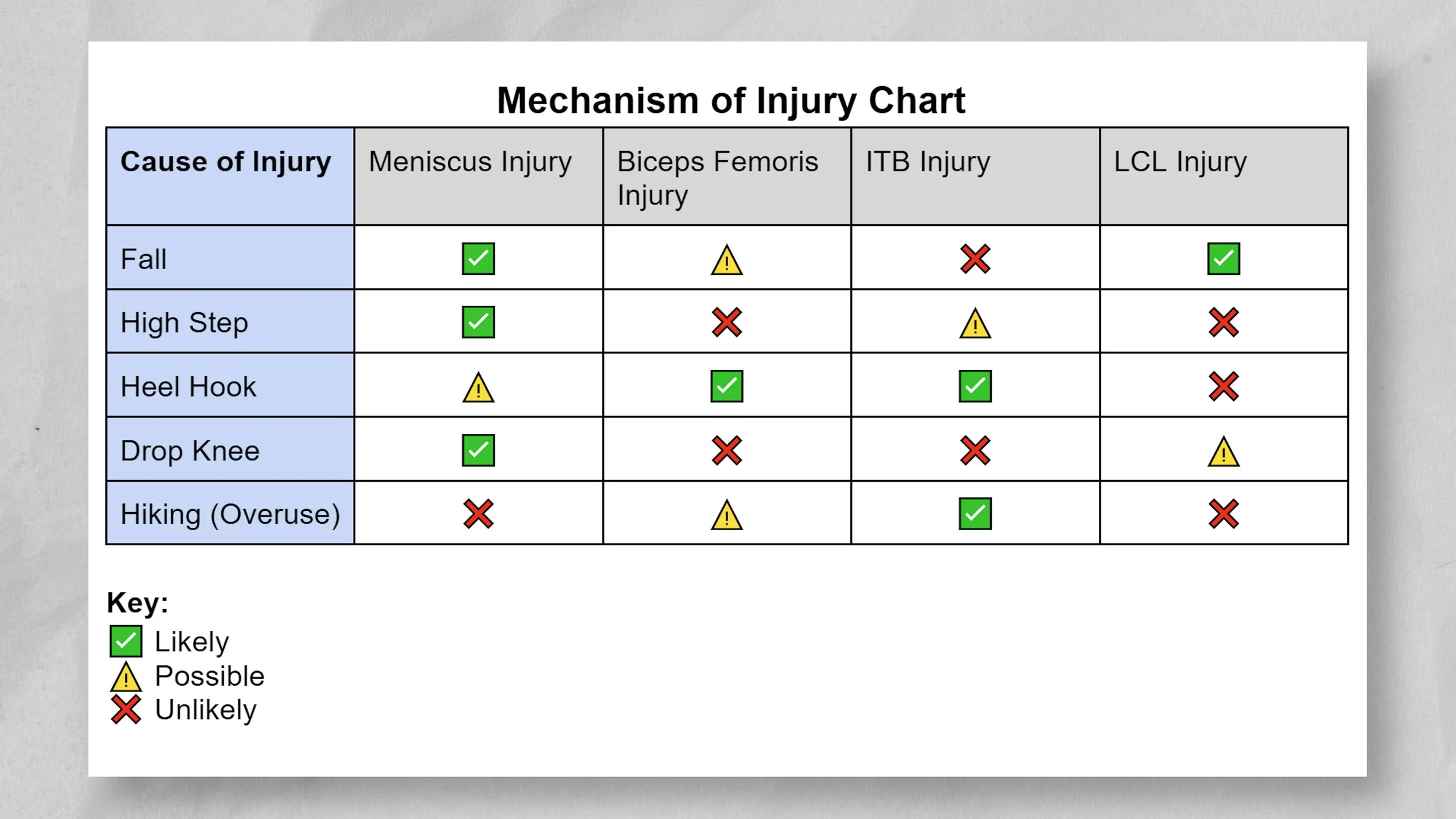

Now, here’s a cool little chart to help you visualize all this information and narrow down what’s causing your lateral knee pain. We can, however, increase our certainty by quite a bit with a few simple tests, which we might as well do now.

DIAGNOSING LATERAL KNEE PAIN

These are the tests you can do yourself, relatively easily, without the help of a professional. However, as always, you should use caution and stop if you’re uncertain or feel more than mild pain.

As a quick note: you’ll notice I mention the “joint line” a few times in this section. The joint line is the outer portion of the joint that you can actually see and touch. The joint itself is the articulating surface between the femur and tibia, which you cannot dig into and reach, but you can indeed inspect the “external” surface of the joint aka the joint line.

Test 1: Resisted Knee Flexion

Start sitting on the ground with your knee bent at 90 degrees (heel on the ground, toes in the air).

Slowly increase the force on your heel, pressing it into the ground.

Note the location of any pain this causes.

If you had no pain, repeat this test with the knee slightly straighter (~120 degrees) and slightly more bent (~70 degrees).

Test 2: Palpation to Specific Locations

While I don’t think palpation should be your “gold standard” for diagnosis in this case, it can still be helpful if we pay close attention to specific locations. Be sure to note your pain levels while doing this.

Starting with gentle pressure and slowly building up, palpate directly at the joint line.

Now palpate below (distal to) the joint line and just behind (posterior to) the knee

Move back to the original position and then palpate above (proximal to) the joint line.

Keep in mind, significant pain can be diffuse, making this test less accurate. If you have that much pain, you should reassess at a later date or, better yet, see a doctor

Test 3: Varus Test

Normally the varus test is reserved for skilled practitioners, but you can do a modified version on your own.

Sit on the ground with your injured leg straight, close to a wall. The outside of your foot should be able to touch the wall but your hip should not.

Gently press the outside of your foot against the wall, stopping if you feel pain or laxity in your lateral knee.

If you don’t feel pain, bend your knee to about 30 degrees and repeat the test.

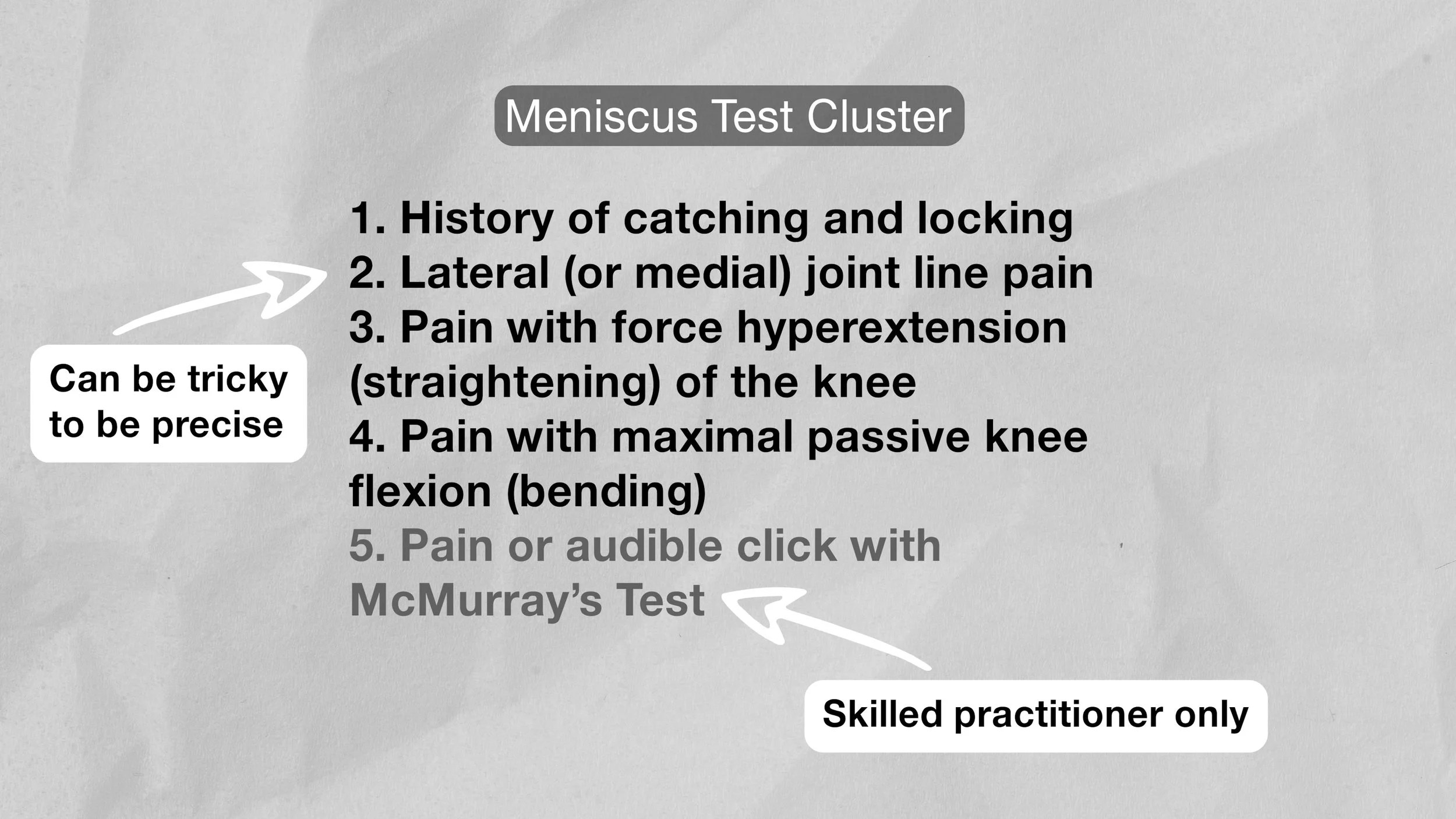

Meniscus Test Cluster

The meniscus test cluster is a group of five tests that can effectively determine how likely you are to have a meniscus injury. Two of the tests require a skilled practitioner to administer, but the remaining three you can perform on your own and can still give you accurate results. The tests are as follows:

If you are positive for three of four of these self-administered meniscus tests, you very likely have a meniscus injury and should seek help from a professional. If you test positive for just one or two of the tests, you may still have a meniscus injury but the chances are lower. Keep in mind, this test cluster does not determine the severity of your injury.

If you were negative to all three tests, there are still other tests that can help diagnose a meniscus injury, but they are more complicated and should be performed with guidance of a professional.

If you have catching and/or locking of the knee and suspect a meniscus injury, please see a professional.

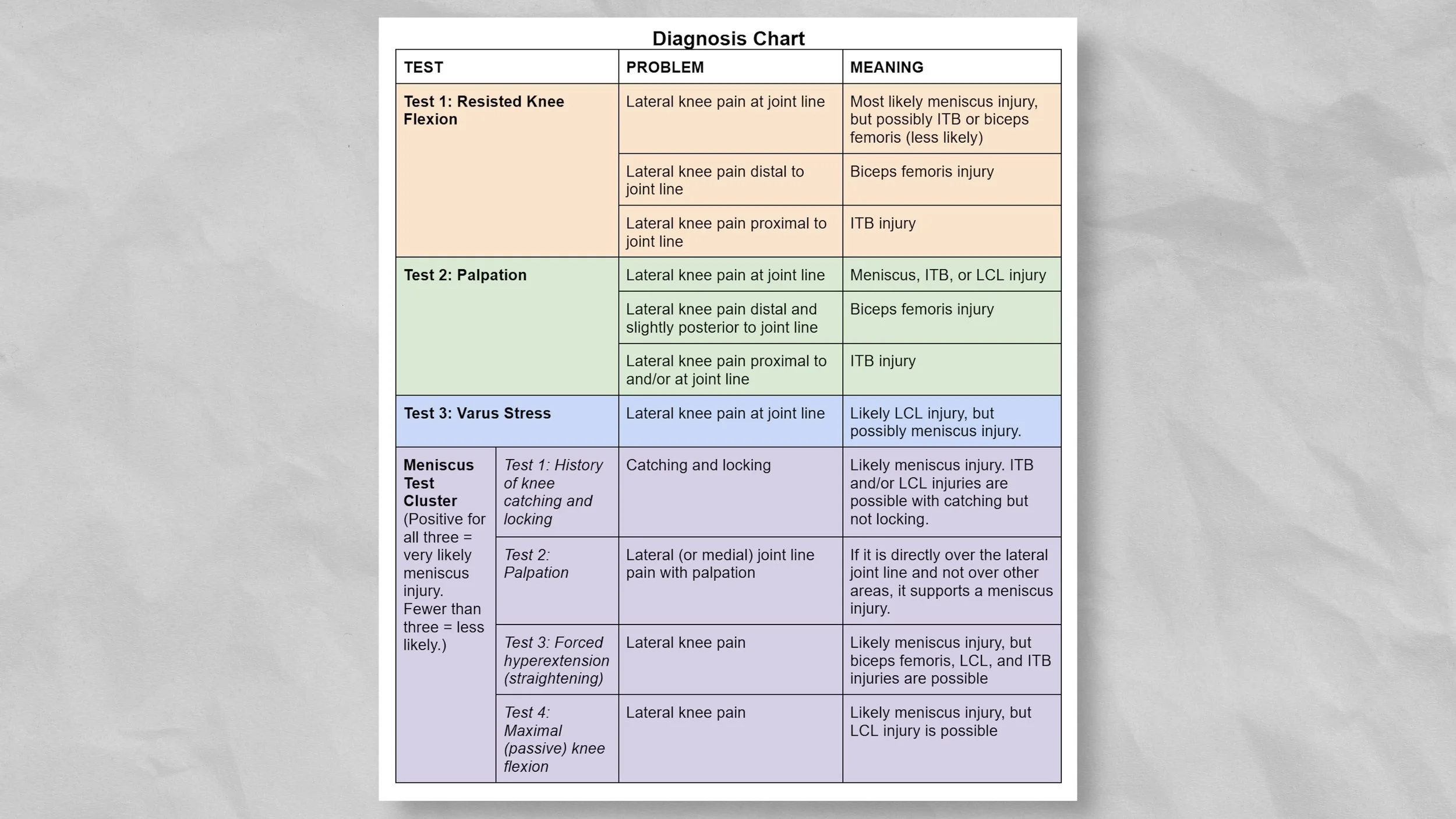

Results

Now that you’ve completed these tests, you should be able to narrow down what is most likely causing your lateral knee pain by comparing your results to this chart. Of course, self-diagnosis is not always easy or accurate, but this should get you on the right track.

HOW DO WE FIX LATERAL KNEE PAIN?

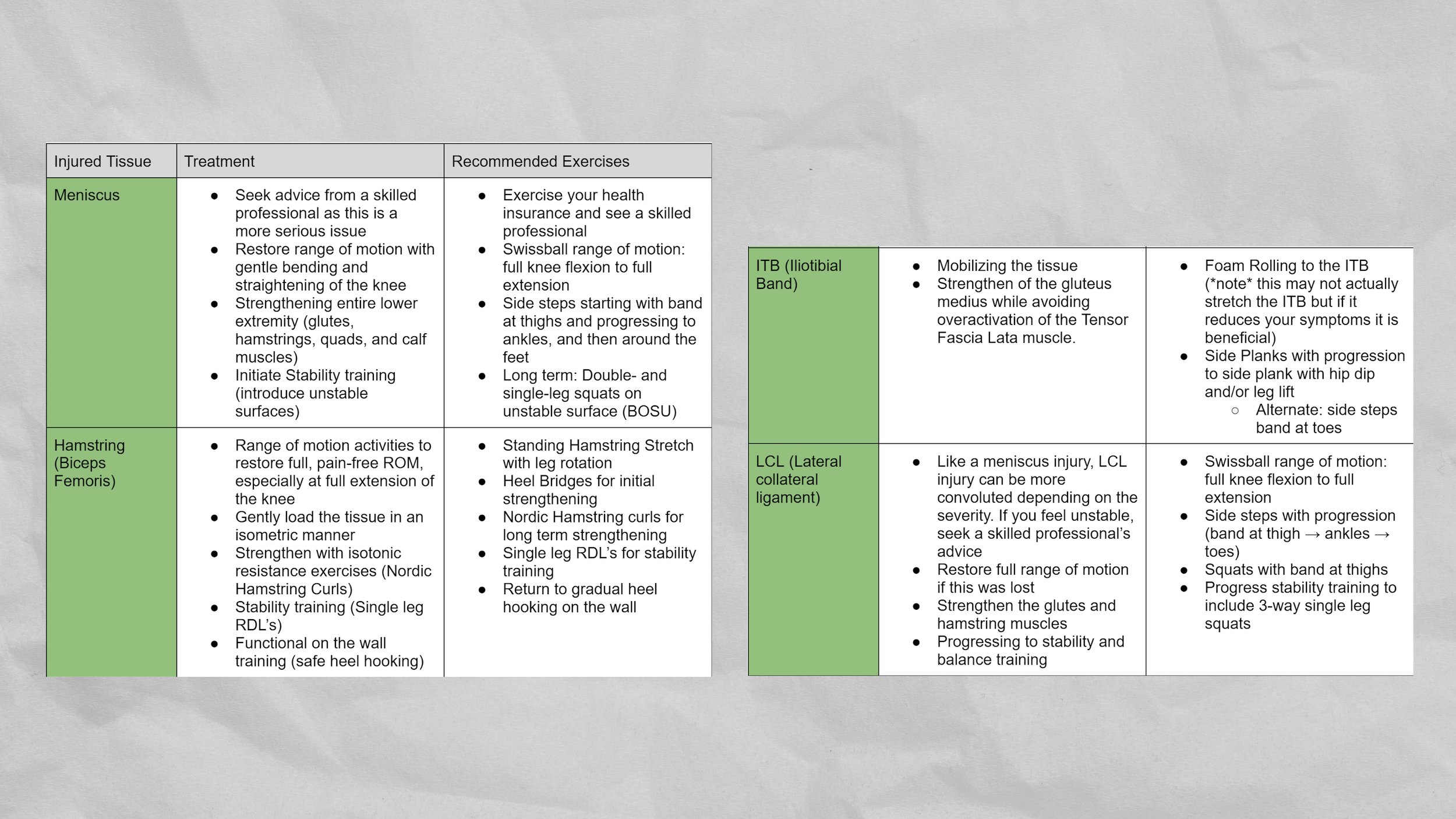

The treatment for lateral knee pain will of course depend on what your specific issue is, though there is often some overlap.

Meniscus rehab will involve range of motion activities with a swissball, side steps with band resistance, and eventually double- and single-leg squats on an unstable surface to improve stability of the lower extremity. If you do suspect a meniscus injury, it’s a great idea to see a skilled professional as this is the most complex to rehab.

Biceps femoris rehab will involve gentle standing hamstring stretches with leg rotation, heel bridges for initial strengthening, then progressive hamstring strengthening such as nordic hamstring curls, single leg RDLs, and gradual return to heel hooking on the wall.

ITB rehab will involve side steps with a resistance band at your toes and/or side planks, progressing to side planks with a hip dip and/or leg lifts. Foam rolling the ITB may also be useful in some cases.

Finally, LCL rehab will involve range of motion activities with a swissball, side steps with resistance band progressions (starting at the thighs, then ankles, and finally feet), squats with band at thighs, and eventually three-way single-leg squats.

As a general rule with all of these rehab activities, you should not really feel any pain with them! But, if you do, there should be no more than about 2/10 pain, and the pain should not linger afterwards. For strengthening exercises, I generally aim for 2-3 sets of 8-12 repetitions, focusing on keeping the repetitions slow and controlled. For stretching, I prefer 2-3 reps of 30-45 second holds. For the range of motion work, perform higher reps (8-10) with 5 second holds at each end.

Since we’re clearly obsessed with organization on this channel, here’s one last chart to get your rehab on track. Most lateral knee injuries can be solved in about 8 to 12 weeks, depending on severity of course. Some injuries can take up to 16 weeks to recover, and recovering full strength may take even longer. If you are not making any progress with your injury in 8 to 12 weeks, though, be sure to reach out to a skilled professional for guidance.

The great thing about these exercises (and knee rehab in general) is after you’ve rehabbed your injury, the same exercises can be used to help prevent a future injury. That’s because us climbers love to ignore lower body training, meaning our muscles and joints are simply too weak and/or inflexible to withstand the forces of climbing. So, basic lower body strengthening will actually prevent most knee injuries from happening in the first place.

OUTRO

Final food for thought: if you’re feeling down about your knee pain, remember that it is a highly treatable condition. In fact, in research by Lutter et al, every one of their participants were able to return to climbing after rehabbing their knee injury.

If you liked this video, hit that like button and let us know what other rehab-related videos we should make! Until next time… train climb send repeat.

RESEARCH

Title

Mechanisms of Acute Knee Injuries in Bouldering and Rock Climbing Athletes

Citation

Lutter C, Tischer T, Cooper C, Frank L, Hotfiel T, Lenz R, Schöffl V. Mechanisms of Acute Knee Injuries in Bouldering and Rock Climbing Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Mar;48(3):730-738. doi: 10.1177/0363546519899931. Epub 2020 Jan 31. PMID: 32004071.

Key Takeaways

Introduction

Josephsen et al reported a higher percentage of knee injuries in indoor bouldering as compared with outdoor bouldering.

This change is explained bymodern climbing and training methods causing a wider spectrum of climbing-related injuries

While 6.7% of all climbing injuries treated in our climbing-focused outpatient clinic in the recent past were knee injuries, other current studies report that up to 10% of total injuries are knee injuries among climbers.

Methods

Between 2015 and 2018, we investigated all athletes (non competitive and competitive) with acute knee injuries related to rope climbing or bouldering (indoor and outdoor)

Knee injuries caused by rope climbing or bouldering activities were defined as medical conditions forcing the athlete to rest from the sport because of pain or dysfunction and the necessity to seek help from a specialist.

Tegner, Lysholm, and climbing-specific scores were used for evaluation of preinjury status of the affected knee

Athletes were asked to describe the exact mechanism of injury (MOI) that caused the pain, based on the body position and activity in the given climbing route and observations of their climbing partners

All patients were seen for follow-up evaluations 6 and 12 weeks after the initial consultation and contacted after 1 year.

Results

During the 4-year period, we treated 71 patients (45 [63.4%] male, 26 [36.6%] female) with 77 independent knee injuries caused by rope climbing or bouldering

Twenty-five (35.2%) of the athletes performed the sport on a competitive level; among those, 15 (21.1%) were World Cup–level athletes.

Only 5 injuries occurred during competition while 66 injuries occurred during training.

Four types of traumatic MOS were identified: the high step position, the drop knee position, the heel hook position, and a fall to the ground. No other MOIs were reported.

An internally rotated hip with a flexed knee characterizes the drop knee position

For improved body positioning, the athlete loads the extremity, which leads to a high mechanical load on the medial meniscus, especially during combined extension and rotation under load

During the heel hook position, the heel is used to apply pressure onto the hold while pulling on the foot by flexing the knee via a strong hamstring contraction. In addition, the knee is rotated laterally, applying a high load to the knee

A fall as a traumatic MOI for severe knee injuries results from uncontrolled falling (eg, load in combination with rotational movements), insufficient ground protection, or insufficient body control owing to fatigue (eg, reduced core stability or limited neuromuscular control causing valgus loading of the knee), even from lower heights

With 46.8% of all injuries, indoor bouldering was the main cause of injury, followed by outdoor rope climbing (26%), outdoor bouldering (22.1%), and indoor rope climbing

The leading structural damage in the knee was a medial meniscal tear, which was the leading diagnosis in 28.6% (n = 22) of all injuries. These injuries were predominantly caused by the high step, drop knee, and heel hook positions.

Iliotibial band sprains were present in 19.5% (n = 15) of all injuries. This type of injury resulted exclusively from heel hook positions.

ACL tears combined with medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus injuries were detected in 9.1% (n = 7) and isolated ACL tears (n = 2) or partial ACL tears (n = 2) in 2.6%.

Ninety-one percent of injuries that caused at least a partial tear of the ACL resulted from a fall to the ground.

Lateral collateral ligament (7.8%; n = 6) or isolated lateral meniscal (5.2%; n =4) tears occurred less frequently.

Outcomes

All athletes had returned to sports within 12 months

Comparison of Traumatic MOIs

High step and drop knee injuries were more common during rope climbing, whereas heel hook and fall injuries were more often caused by bouldering.

Patients who were injured during a heel hook had the highest ability level, and patients injured during a fall had the lowest bouldering ability level

Patients who were injured during a heel hook had the highest training volume per week (15.1 hours), while athletes from the drop knee group had the lowest (11.2 hours).

No significant difference in traumatic MOI was found between groups, although medial meniscal tears were significantly more frequent in noncompetitive athletes. Surgical procedures were required significantly more often in the noncompetitive group as compared with the competitive group

Discussion

The majority of knee injuries in our study (47%) happened while indoor bouldering, even though both study centers are located in regions known for 8 their famous outdoor rope climbing

In total, injuries caused by bouldering activities represented 69% of all knee injuries within our study, which strengthens the theory that bouldering seems to be more prone to causing knee injuries than climbing with a rope.

In our study, knee injuries caused by a fall had a significantly higher UIAA score than injuries from other trauma mechanisms and were predominantly found in female athletes. Furthermore, those injuries were mainly found in athletes with less experience and potentially less body control and stability strength while landing

liotibial band sprains at the lateral condyle were caused exclusively by heel hook positions

the iliotibial band is fully tightened and eventually glides over the lateral condyle of the femur under tension.

All ACL tears within our study group happened in cases of uncontrolled falls onto the ground.

Medial meniscal tears were predominantly caused by the high step, the drop knee, and the heel hook positions

The heel hook technique rather causes a shear stress to the menisci by a slightly flexed but fully loaded knee under tension

The athlete stresses the leg in a fully flexed knee in the drop knee and high step positions (see Figure 1, A and B), causing a high load on the meniscus

That athletes experiencing knee injuries while performing a heel hook had a high climbing or bouldering level as well as a high weekly training workload might strengthen the theory that stronger climbers use this technique more aggressively than others and thereby injure the knee.

For all 3 MOIs, a peak load is suspected to cause the injury

We suspect injury-causing events for the drop knee and high step positions to be different. In both body positions, we can assume that the injury happens within the moment when the athlete releases one hand to reach the next hold, leading to an extra load on the lower extremities.

Furthermore, insufficient technical skills and fatigue might cause harmful rotational motion of the knee in experienced athletes.

Rope climbing on an overhanging wall has been described as having a lower injury risk for the lower extremitie and should therefore be preferred to rope climbing on vertical walls. Falls on overhangs are stopped exclusively by the rope, whereas falls during rope climbing on a vertical wall can cause a swing into the wall.

Most climbers neglect the leg muscles completely in their training routine.

Title

Evidence Summary: Hiking/Mountaineering. Active & Safe Central

Citation

Krolikowski M, Black A, Richmond SA, Babul S, Pike I. Evidence Summary: Hiking/Mountaineering. Active & Safe Central. BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit: Vancouver, BC; 2018. Available at http://activesafe.ca/

Key Takeaways

Injury rates have been reported as 6.1 injuries/1000 participant days (95%CI: 1.2-18.7) for mountaineering. Another study reports injuries at a rate of 0.56 injuries/1000 hours

Disclaimer:

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com

IG: @emile166