How to Fix Nerve Tension for Climbers (Nerve Impingement, Nerve Pinching)

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 69

INTRO

Have you ever told someone “hey, you’re getting on my nerves?” Well I’m about to get alllll up on those nerves. as we talk about neural tension. This video and article will cover some basic anatomy of the nervous system, causes and symptoms of neural tension in the upper extremities, testing, possible misdiagnoses, treatments, and we’ll answer some questions submitted by you, our subscribers!

Let’s start by learning what neural tension is and what causes it in the first place.

CAUSES OF NEURAL TENSION (ETIOLOGY)

Neural tension, otherwise known as nerve entrapment, is an abnormal physiological and mechanical response created by the nervous system when its normal range of motion or stretch capacity is limited. Lack of nerve mobility can be caused by compression from tight, swollen, or scarred surrounding tissues. The location of this compression is called an “entrapment site,” which is why neural tension is also referred to as “neural entrapment.”

Think of a string threaded through a straw. The string is your nerve and the straw is the surrounding tissue. If you pull either end of the nerve, it glides smoothly through the tissue. But if you pinch the tissue and pull the nerve again, the nerve becomes entrapped and can no longer move smoothly.

The resulting pressure and tension on the nerve is, well, not appreciated, so it responds by producing symptoms such as numbness, tingling, pain, burning, and more.

The reason this is important for climbers to understand is because it can easily be misdiagnosed as tennis elbow (lateral tendinopathy) or climber’s elbow (medial tendinopathy), which are two of the most common overuse pathologies in climbing. And if you don’t have the right diagnosis, you won’t be able to treat your injury and recover. In fact, you could even make things worse.

Now that we know what causes neural tension, let’s jump into the anatomy so we can get our “biological bearings.”

ANATOMY REVIEW

Reviewing some basic anatomy will be helpful in diagnosing which nerve is causing your issues, which we’ll have tests for later in the video. Don’t worry about memorizing all this stuff, you can always come back to reference this section and we’ve got all this written out in the show notes on our website (link in the description!).

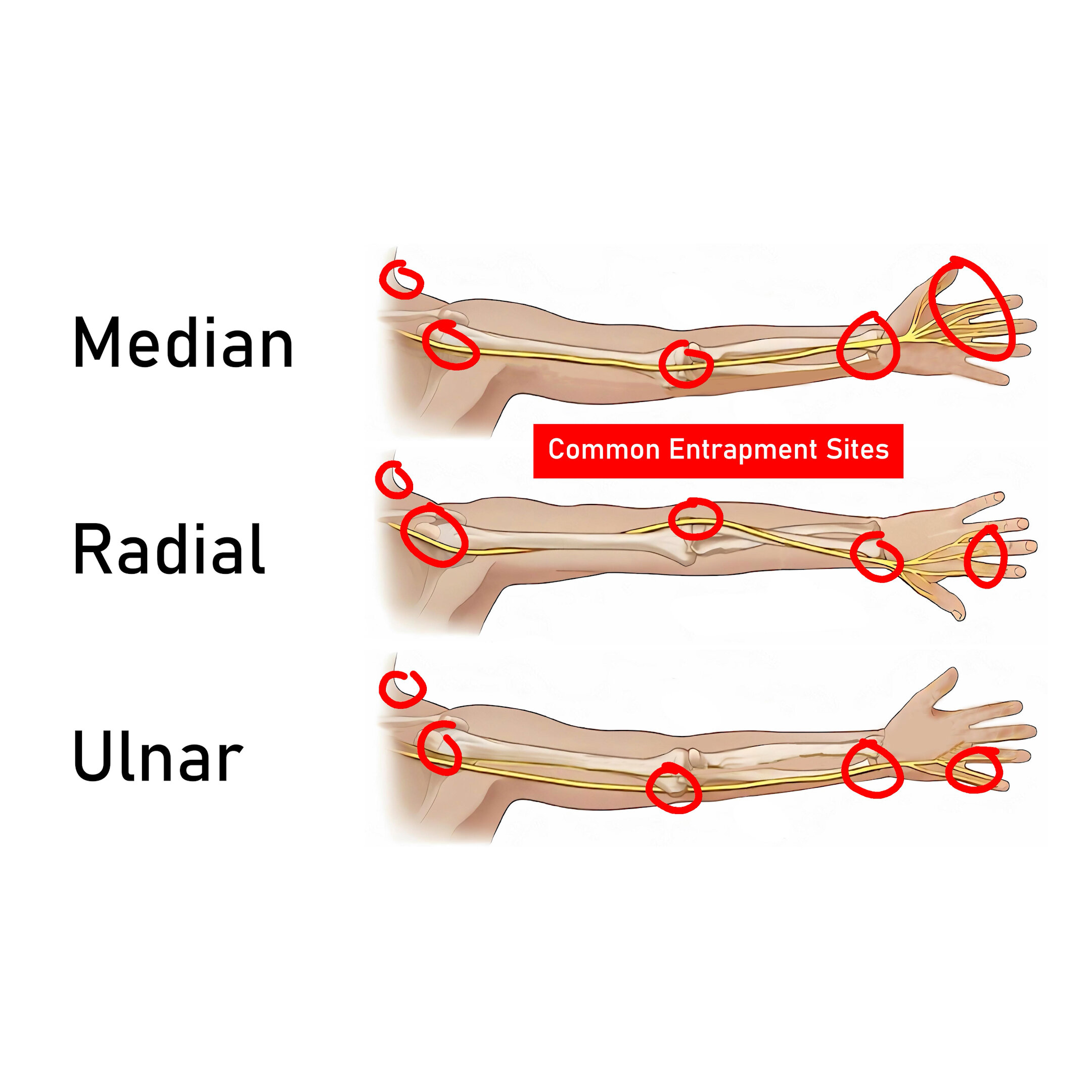

So, the three nerves to be aware of here are the Median, Radial, and Ulnar nerves. These are the three main nerve branches that can become entrapped and cause issues for climbers (and the general population).

All three of these nerves technically originate from your spinal cord, but don’t really branch off and become the median, radial, and ulnar nerve until they move through the brachial plexus at the shoulder.

Once they branch off from the brachial plexus, they move in different areas of your arm to innervate muscle all the way down to your fingers.

Median Nerve Anatomy

The median nerve has roots from the cervical and thoracic spine, C6, C7, C8 and T1. It leaves through the brachial plexus in the armpit (the axilla) and descends down the arm just near the brachial artery (so on the inside aspect of your arm). It passes through the antecubital fossa deep in relation to the biceps aponeurosis (also called the lacertus fibrosus) and anterior to the brachialis muscle. The median nerve runs between the superficial and deep heads of the pronator teres at the elbow. It enters the anterior compartment of the forearm by passing beneath the fibrous arch of the heads of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle.

In the forearm, it travels down the middle of the forearm and then into your hand. It innervates the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and half of the 4th digit.

Entrapment sites: The median nerve can be entrapped at four locations around the elbow:

1) the distal humerus by the ligament of Struthers,

2) the proximal elbow by a thickened biceps aponeurosis,

3) the elbow joint between the superficial and deep heads of the pronator teres muscle (which is the most common cause of median nerve compression), and

4) the proximal forearm by a thickened proximal edge of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle.

I would highlight the pronator teres muscle, as it’s the most common entrapment site, as well as the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle, it’s one of the main finger muscles we use for climbing and as such is prone to irritation.

Radial Nerve Anatomy

The radial nerve also has roots from the cervical and thoracic spine, C6, C7, C8 and T1. It travels down the backside of the humerus or upper arm before moving to the anterior or front aspect of the outside of the elbow. So… here! The radial nerve splits here but travels alongside the brachioradialis muscles. The radial nerve splits through the supinator muscle between the deep and superficial heads. It courses into the dorsum or backside of the hand where it provides sensation to the proximal aspects of the dorsum of the thumb, index finger, and middle finger

Entrapment Sites: The radial nerve has 5 compression sites…. I’m not going to go over all of them in this video, but be sure to check out the website with the show notes for details on each!

Deep branch radial nerve compression may occur at five different locations within the radial tunnel from proximal to distal [24]:

1) the level of the radial head by fibrous bands between the brachioradialis muscle and joint capsule,

2) distal to the radial head by the leash of Henry, an arcade of anastomosing branches of the radial recurrent artery,

3) the level of the tendinous edge of the overlying extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle,

4) the arcade of Frohse along the proximal aspect of the supinator muscle, and

5) the distal aspect of the supinator muscle.

I will mention here, though, that the arcade of Frohse is the most common site of compression and is due to thickening of the connective tissue near the edge of the supinator muscle, specifically the superficial head of the supinator. Normally, the edge is thin. Thickening of this edge is developmental, most likely due to repetitive pronation–supination.

Oh my gosh. OK, so too much supination and the radial nerve suffers, too much pronation and the median nerve gets punished. It’s like a nerve police state over here! Pronation? Right to jail! Supination? Believe it or not…

Ulnar Nerve Anatomy

The Ulnar nerve only has branches from C8 and T1. It runs down the medial or inside of the humerus until it enters the posterior aspect as it nears the elbow. It lies anterior and medial to the triceps muscle. The ulnar nerve passes posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus in the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel is a fibro-osseous channel formed by the olecranon process laterally, the posterior cortex of the medial epicondyle medially, the elbow joint capsule and posterior bundle of the medial collateral ligament anteriorly, and the ligament of Osborne (the cubital retinaculum) posteriorly (Fig. 1). Within the tunnel, the ulnar nerve is normally surrounded by fat. The nerve exits the distal aspect of the cubital tunnel to enter the medial aspect of the forearm between the superficial and deep heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. It runs down into the hand and innervates part of the 4th and most/all of the 5th digit.

Entrapment Sites: Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is the second most common nerve entrapment of the upper extremity, after carpal tunnel syndrome. Flexion of the elbow causes

increased tensile load on the ulnar nerve, particularly at the elbow and also increases pressure within the cubital tunnel by up to 20 times the pressure at rest! So, imagine a locked off position and trying your absolute hardest, definitely possible to recreate a lot of pressure there!

Based on this information, we can see there are five locations that may develop upper extremity neural tension: the neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers.

OK, before we freak you out: Don’t worry, we aren’t all doomed to have nerve entrapment just because we are awesome rock climbers. Also, just because we get nerve entrapment, doesn’t mean we are stuck with it forever! I personally have dealt with radial nerve entrapment and it has been gone for years now! So let’s keep cruising here and delve into the symptoms.

SYMPTOMS OF NEURAL ENTRAPMENT

Symptoms of neural tension can be challenging to accurately identify due to the varying sensations you may experience and the location of them.

They can present as mild tingling or a decrease in sensation, but they can also be more advanced with numbness, burning, and/or pain, such as a dull ache. The symptoms may be position dependent as well, meaning they may come and go quickly with positional changes of your upper extremities. On the other hand, some symptoms can linger for long periods of time due to unresolved compression of tissue.

As for location, symptoms may present in the upper arm, but they most often occur at the elbow, wrist, or hand, so we will focus on those. It may be isolated to one of the areas I mention, but multiple sites may be involved as well.

Ulnar nerve irritation may present with isolated symptoms by the inside of your elbow, on the inside of your wrist, or to your 4th and 5th fingers. But, it is also possible to have symptoms at all 3 locations simultaneously. The same is true for the radial and median nerve.

The radial nerve may cause symptoms on the outside of your elbow and can travel down the outside of your forearm to your wrist and into your thumb and possibly the back side of your hand and index finger.

The median nerve may present with symptoms on the inside and anterior / front part of your elbow and forearm. It may travel down the forearm and go into your palm and fingers.

The exact location of symptoms may vary slightly from person to person, as everyone’s nerve distribution can vary slightly. However, the general path we described is accurate for most cases and any variances will be subtle.

Alright so now that we’re familiar with the symptoms, let’s take a look at the tests we use to diagnose neural tension.

ABOUT NEURAL TENSION TESTING

Diagnosing neural tension is done primarily through neural tension testing. The testing evaluates the length and mobility of the nervous system with progressively increasing amounts of tension on specific nerves, reproducing symptoms in a controlled manner. This progression is achieved by specific movements in the five locations that may develop upper extremity neural tension: the neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers.

There are four primary neural tension tests for the upper extremities, called “Upper Limb Tension Tests” or ULTTs. There are two for the median nerve, one for the ulnar, and one for the radial. These tension tests are typically done with a skilled provider but they can be done yourself if you move slowly and pay close attention to proper technique.

We’re going to talk about each test in a second, but first we need to understand the three important rules of neural testing.

TESTING GUIDELINES

Okay, rule number one of neural tension testing: you should always do this on your unaffected side first in order to create a baseline. Why? Because many of you may find you have some level of neural tension. In fact, studies have shown a majority of people have a positive ULTT1 for the median nerve. This doesn’t mean that most of the population has a dysfunction of their nervous system; it is just our normal anatomy. So, rule #1: a TRUE positive neural tension test only occurs if the affected arm has greater/more intense symptoms than the unaffected arm.

Now, rule number two is equally important: a neural tension test is only positive if it recreates or exacerbates the approximate symptoms that led you to do the test in the first place. So, say you want to find out why you have pain on the outside of your elbow. You do the neural tension tests and one of them causes some tingling in your thumb. That is not a positive test for your symptoms, as it did not recreate or exacerbate your outer elbow pain (or something very similar to it). You may have some mild neural tension, but it is likely not the cause of your elbow pain in this instance.

Finally, bonus rule number three, and this is really more of a suggestion: do these tests in the order I am presenting. Again, the point is not to aggravate your nerves too greatly, but rather, to recreate symptoms in a controlled manner. Don’t rush through the tests. If you start to recreate your symptoms, you can stop there. You don’t need to create further tension on the nerve as that may just create further irritation.

OK, on to the tests.

DISCLAIMER: Quick disclaimer: this video is not meant to diagnose or treat thoracic outlet syndrome, cervical radiculopathy, or carpal tunnel syndrome. Those are completely different nerve-related issues. However, if you’re unsure what pathology you’re dealing with, it is safe to perform the tests in this video to help determine whether or not nerve entrapment applies to you.

UPPER LIMB TENSION TESTS

All tests should be done in a standing position:

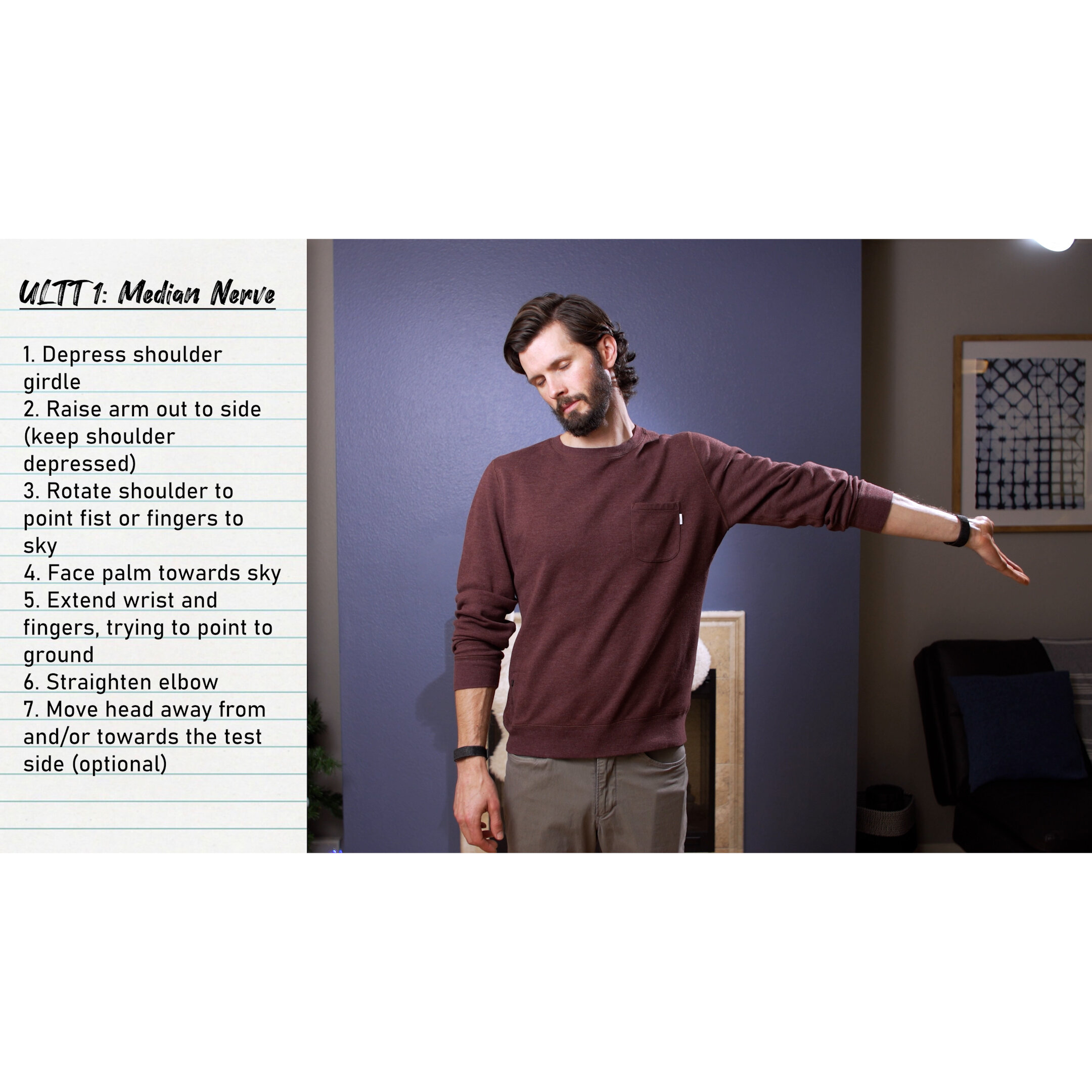

Upper Limb Tension Test 1: Median Nerve

Shoulder girdle depression

This is the exact opposite of a shoulder shrug.

Shoulder abduction

After raising your arm out, you will likely need to depress your shoulder again. If the shoulder is shrugging, the results will not be accurate

Shoulder external rotation

Basically, rotate your arm until your fist is up to the sky

Forearm Supination

Your palm should now be facing towards your head

Wrist and Finger extension

The position now is as if you were carrying a pizza

Elbow extension

Straighten the elbow out

This is where MOST people will start to feel symptoms

Cervical side flexion

This is the key here

Moving your head TOWARDS the shoulder should RELIEVE symptoms.

Moving your head AWAY from the shoulder should INCREASE symptoms

Do this SLOWLY. We don’t want to stretch the nerve too hard if there is tension present.

Upper Limb Tension Test 2: Median Nerve

Shoulder girdle depression

Elbow extension

Lateral rotation of the whole arm

Wrist, finger and thumb extension

Cervical side flexion / rotation

Upper Limb Tension Test 3: Radial Nerve

Shoulder girdle depression

Elbow extension

Medial rotation of the whole arm

Wrist, finger and thumb flexion

Cervical side flexion / rotation

Upper Limb Tension Test 4: Ulnar Nerve

Shoulder girdle depression

Shoulder abduction

Shoulder external rotation

Wrist and Finger extension

Elbow flexion

Cervical side flexion / rotation

TEST RESULTS

If you followed the testing guidelines and are positive for any of the ULTTs, you can go even more in-depth by isolating different steps in the test to see if one causes more symptoms than another.

To help explain this, take the second test for the median nerve as an example.

I depress my shoulder girdle, extend my elbow, rotate my entire arm, and then extend my wrist, fingers, and thumb. In this position I feel some tingling, but what’s causing it? I’ll maintain this position, but allow my hand to go back to a natural, limp position. Now I notice my symptoms decrease. But when I extend again, BAM, symptoms are back. Now I’ll move on to my elbow. I bend it, then extend it back again, and notice my symptoms decrease and then increase again as I do. What about my shoulder? I shrug my shoulder and all my symptoms go away. And the minute I depress again, wow, I really feel it. That is all information I can use to determine which locations have entrapment, which can be useful for treatment. If you notice one spot is particularly more aggravating than another, that may be your site of entrapment.

But, what happens if multiple sites are equal? What if the hand, elbow, and shoulder movement all recreated the symptoms equally. Well, it could be that you have multiple entrapment sites, you just have a slight shortening of the nerves, or, it could just be that where you feel the pain is entrapping the nerve enough to create symptoms regardless of where the movement comes from. It’s just tight and irritated! No matter; you’ll be able to overcome these issues with the treatments we’re going to talk about in a bit.

But, before we get to treatment, let’s talk about one of the most important sections, one of the main reasons you were drawn into this video, misdiagnosis!

MISDIAGNOSIS

I mentioned earlier that nerve issues are not isolated to just neural tension. You could have a cervical radiculopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, etc. For that reason, this section could go on FOR A WHILE! So to keep us focused on what’s most relevant for climbers, we’re going to limit this discussion to two misdiagnoses: lateral epicondylopathy (tennis elbow) and medial epicondylopathy (climber’s elbow).

Distinguishing between neural tension and climber’s or tennis elbow is difficult because of similarities in the location of symptoms and the symptoms themselves.

Climbers elbow causes pain at the medial elbow and sometimes when the symptoms are bad it can be in the anterior forearm as it follows the muscles of the wrist and finger flexors…. Median nerve entrapment also causes pain at the medial elbow and also when irritated more can cause symptoms down the anterior forearm.

Tennis elbow causes pain at the lateral elbow and when irritated can cause symptoms on the backside of your forearm…. I’ll let you guess what I’m going to say next about radial nerve entrapment… OK fine no guessing. It can also cause pain in those exact same locations.

Dang! Not cool, right? Same locations??? And to make things even more complicated? Sometimes nerve entrapment only causes a dull ache. You know what else causes a dull ache? Climbers elbow and tennis elbow!

So now what do we do?

Well, for one: nerve issues are more likely to produce radicular, or traveling, pain. So if you have pain that travels all the way into your hand there’s a hint that a nerve might be to blame. Other than that?

Sometimes, you have to use your treatment as your diagnostic tool. So check this out: if you aren’t positive you have neural tension, but you do some neural tension treatment exercises and you start to feel better, that treatment just became your diagnostic tool. Treating neural tension will not fix tennis elbow or climber’s elbow, so you likely had neural tension all along.

Now I know we’re going over a lot of details in this video. If you feel completely lost at this point or just don’t want to do all this testing and diagnosing on your own, I highly recommend seeing a PT, MD, or even a neurologist if your symptoms are bad enough! I know it’s annoying but it can actually end up saving you time and stress in the long run.

Shameless plug: If you want to see a PT but don’t know any, you can always book a private session with me on our website at www.hoopersbeta.com/private-sessions.

On the other hand, if you feel confident you have neural tension at this point OR you’re ready to use neural tension treatment as a diagnostic tool, then you’re ready for the next section!

TREATING NEURAL TENSION

When it comes to treating neural tension, there are two primary and a few secondary forms of treatment. The two primary forms of treatment focus on improving neural mobility. This is accomplished with nerve gliding and nerve tensioning.

Nerve Gliding

Nerve gliding is like it sounds, you are gliding the nerve through it’s pathway to help reduce any possible adhesions, sites of entrapment, etc. This is also referred to as “nerve flossing.” Think back to the string-through-a-straw example that we used earlier.

With nerve gliding, you pull one end of the nerve while relaxing the other, and then vice versa. Nerve gliding smoothes out internal surfaces, breaking up any scar tissue or sites of entrapment, so the more you do it the smoother the nerve’s “pathway” becomes. This is a non-aggressive form of treatment as it does not create tension on the nerve IF done correctly.

Performing a Nerve Glide

To perform a nerve glide, you will go through a similar process to your testing, but instead of moving your head AWAY from the test side, you will move it TOWARDS.

Median Nerve Glide

There are two median nerve glides

Choosing which median nerve glide you do is about which one felt more positive with your testing. It is OK, though, to try both and see which form of treatment feels better to you!

To perform the first median nerve glide, perform the following steps

Rest your arm by your side with your elbow straight

Rotate your arm so that your palm faces forward

Reach your hand down towards the ground, while keeping your chest/torso upright

Extend your wrist, point your fingers behind you while simultaneously bring your head towards the same side (if you are moving your left arm, move the head to your left)

Bring your hand back to neutral while simultaneously moving your head away (towards the opposite arm).

Repeat x10

Hold for 0-1 seconds

To perform the second median nerve glide, perform the following steps

Raise your arm out to the side with your elbow straight until it is parallel to the ground (90 degrees of abduction)

Rotate your arm until your palm is up

Depress your shoulder down (opposite of shrugging), while keeping your chest/torso upright

Extend your wrist, point your fingers behind you while simultaneously bring your head towards the same side (if you are moving your left arm, move the head to your left)

Bring your hand back to neutral while simultaneously moving your head away (towards the opposite arm).

Repeat x10

Hold for 0-1 seconds

Radial Nerve Glide

To perform a radial nerve glide, perform the following steps

Rest your arm by your side with your elbow straight

Rotate your arm so that your palm faces backwards

Extend your arm about 10-15 degrees behind you

Reach your hand down towards the ground, while keeping your chest/torso upright

Flex your wrist, pointing your fingers behind you while simultaneously bring your head towards the same side (if you are moving your left arm, move the head to your left)

Bring your hand back to neutral while simultaneously moving your head away (towards the opposite arm).

Repeat x10

Hold for 0-1 seconds

Ulnar Nerve Glide

To perform an ulnar nerve glide, perform the following steps

Raise your arm out to the side with your elbow straight until it is parallel to the ground (90 degrees of abduction)

Rotate your arm until your palm is down

Depress your shoulder down (opposite of shrugging), while keeping your chest/torso upright

*now it gets tricky, we have to coordinate 3 movements*

Bend/flex your elbow, extend your wrist, and bring your head towards the same side (if you are moving your left arm, move the head to your left)

Reverse: Straight your elbow, relax your hand, and move your head away (towards the opposite arm).

Repeat x10

Hold for 0-1 seconds

I usually say start with one set of ten glides with no hold at the end of the movement. Remember, you are pulling the string back and forth through the straw, so to speak, so you don’t need to pause and hold for a long time on either end. You can do this two times a day initially. And if you find it to be beneficial after the first couple of days, you can increase to three times a day.

Nerve gliding has actually been studied in cadavers and is shown to create movement of the nerve throughout its pathway. It is effective! The reason I mention this is because with nerve gliding, you should actually feel… nothing! This can be confusing, because usually we expect to feel something when we perform an exercise, even if it’s just a dull burn or some tension. Rest assured, however, that feeling nothing while nerve gliding is exactly what we want.

Now, if you don’t find nerve gliding to be effective after the first week or so, it’s time to move on to the next primary treatment: nerve tensioning.

Nerve Tensioning

Nerve tensioning is also just like it sounds: you create tension, or a stretch, on the nerve. This should be your second step, not the first. Nerve gliding is not aggressive whereas nerve tensioning can be more aggressive. The reason this is more aggressive is because nerves simply don’t love being stretched. Nerve tensioning is meant to aggressively mobilize your neural network and attempt to improve mobility while reducing adhesions.

To perform nerve tensioning you simply do, well, the opposite of the nerve gliding. You move the head AWAY from the side you are mobilizing, which creates more tension.

With most stretches we do to our skeletal structure, we’ll often hold for 15, 30, 60 seconds in certain positions without issues. Not so with nerve tensioning. The MAXIMUM time we want to hold a nerve tension stretch is 5 seconds.

Unlike nerve gliding, you WILL feel this, so be more cautious as there is a chance you can cause a temporary increase in symptoms. If you go too hard too quickly, you may even cause a small setback by irritating the nerve. For this reason, I recommend starting with only one set of six repetitions, holding for four to five seconds per rep. If this feels like it is benefiting you and reducing your symptoms, you can increase up to ten reps and multiple sets a day.

Secondary Forms of Treatment

Secondary forms of treatment include mobilizing the tissues that surround the affected nerve’s pathway and/or entrapment site! This can be done with massage, instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization (IASTM), myofascial decompression (MFD), or simply with stretching.

Mobilizing the tissues in this way can relieve compression on the nerve or simply break up any adhesions that are affecting it, which can release the tension and reduce or eliminate your symptoms.

These secondary forms of treatment can be done in conjunction with the primary form of treatment of nerve gliding or tensioning, and if done properly should have little to no negative side effects. The positive: you mobilize your tissue, break up any adhesions, and help restore normal function. This is beneficial even if you don’t have neural tension! The only side effect: if you are too aggressive and don’t really know what you’re doing you could irritate the area further. So as a general rule of thumb, when implementing these secondary forms of treatment, start gently and increase the pressure only if you experience positive effects such as decreased symptoms!

My personal favorite secondary form of treatment is MFD or myofascial decompression. This is because it not only mobilizes the tissue but allows you to do nerve gliding simultaneously! Win win! MFD combined with nerve gliding, of course, should be done with caution, or ideally, with guidance of a skilled professional. Again, you don’t want to go too aggressive with this and aggravate your nerves.

And that’s it for neural tension treatment! Now that we know what to do, let’s check our prognosis.

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis is fairly good with nerve entrapment, as you should see changes quickly if you're implementing the right treatment. If neural gliding is going to benefit you, you’ll know in as little as a day or at most two weeks. If nerve tensioning is the way for you, same timeline. However, it may take quite a bit longer to fully recover and that timeline will vary from person to person.

Oftentimes simply mobilizing the neural network or identifying and mobilizing the tissue that is causing the entrapment will be sufficient. The only problem with neural tension is that you can’t really lengthen your nerves. So you will likely need to monitor this in the future and continue to be diligent about your neural mobility even if you feel you are healed, because there is a chance it can return. That may mean continuing to do neural flossing once or twice a week, or staying consistent with whatever stretch was originally effective for you. If you stay on top of it, you can definitely resolve your neural tension issues and keep them away!

QUESTIONS / VIEWER QUESTIONS

Safe to climb?

If you have major symptoms, I don’t recommend it, otherwise yes you are safe to climb if you have neural tension. I have it throughout my body (lucky me) and I still climb (or at least I try to)

Is neural tension dangerous?

Neural tension can lead to long term issues but typically does not. If it goes untreated, it will cause more pain, discomfort, and decrease in function to the point where someone WILL seek professional help before it gets too bad.

What if I do these treatments and it doesn’t go away?

First, self evaluation may not be working and you may need to go see a professional to really diagnose your issues.

Second, there’s always the possibility that it is multifactorial. You may have a tendinopathy that will cause an entrapment of the nerve and you may need to rehab that issue before the nerve issues will resolve.

This can be especially true if it is an entrapment from the pronator teres. This is oftentimes weak in people and weakness can cause tightness, tightness can cause entrapment. So we may need to strengthen and lengthen the pronator teres before the nerve issues will resolve. Again, this may point back to step 1: you may need a professional evaluation.

Can it lead to other issues if left untreated?

Certainly. It can lead to more intense neural symptoms including numbness and tingling and eventually can lead to loss of strength.

If there is a loss of strength it can cause compensations and subsequent injuries of other muscles related to those compensations

Can it go away on its own (without treatment)?

If it is mild, yes. If it is a mild tendinopathy that caused the swelling, once that goes down or away, the tension may also go away.

The body *wants* to heal, so it will try it’s best to heal regardless of what you do. But we can guide that process and make sure it does heal!

If you hurt a nerve once, will it be a chronic issue for you? - probablyclimbing

Not necessarily, no. I had radial nerve entrapment but it was related to a bout of lateral elbow pain. I treated both, and they went away.

I’ve also worked with climbers who have had acute issues with this both median and radial nerve, it went away and has stayed away just with some light continued neural mobility work.

Should you do nerve glides to do before loading tendons - Dcyr19

If you have a history of neural tension, it’s a fine addition to your warm up to do a set of nerve glides.

Is it bad to sleep on your side if you have nerve pain? Bread_rocks_

Unfortunately the answer is, it depends. If it’s in your shoulder, it could be hard if you are sleeping on that shoulder. If it is in your elbow, it may be fine.

Every so often I get an electrical tingle feeling in my right arm/elbow. Am I broken? -vincecong

Vince, you’re perfect, don’t worry.

Is it related to activity? If so you may just be “trying hard”, activating those muscles, and causing the compression → tingling / electrical sensation

Can neural mobes reduce muscle spasms in my shoulder associated w/ gastons/lock offs? Sfjords21

Possibly? Especially with the lock off it may be compressioning your brachial plexus, but it could also just be the strain and stress of the position on your shoulder if you don’t have the proper strength to do so.

How do I stop nerve pain from top of my neck to my shoulder and down my arm? @audreyjps

That sounds more like either a muscle issue, muscle + nerve issue, or a cervical issue such as a cervical radiculopathy. Ask your physician for a referral to physical therapy and see if they can help!

RECOMMENDATIONS AND OUTRO

The most important recommendations are to be patient and be diligent. Some people will be fortunate and get relief after just a day or so, but others may take longer. Be diligent with your exercises, pay attention to the feedback your body gives you, write it down, and be patient. Sometimes it’s hard to track what’s working and what’s not, but if you write it down you’ll get a clearer picture.

And above all, remember: your body wants to heal, you just need to guide it to success. If you don’t feel comfortable being that guide, go see a professional! That’s what they’re there for, after all.

Until Next time…

Train. Keep your nerves mobile. Climb. Don’t let other tissues put pressure on them. Send. Watch super long technical videos on neural tension that took 50 hours to make but will only get like 20 views. Repeat.

RESEARCH

TITLE

Radial Nerve Entrapment

CITATION

Buchanan BK, Maini K, Varacallo M. Radial Nerve Entrapment. [Updated 2020 Jun 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431097/

TITLE

Nerve entrapment syndromes of the elbow, forearm, and wrist.

CITATION

Miller TT, Reinus WR. Nerve entrapment syndromes of the elbow, forearm, and wrist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Sep;195(3):585-94. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4817. PMID: 20729434.

TITLE

The validity of upper-limb neurodynamic tests for detecting peripheral neuropathic pain

CITATION

Nee RJ, Jull GA, Vicenzino B, Coppieters MW. The validity of upper-limb neurodynamic tests for detecting peripheral neuropathic pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 May;42(5):413-24. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.3988. Epub 2012 Mar 8. PMID: 22402638.

TITLE

Frohse's arcade is not the exclusive compression site of the radial nerve in its tunnel,

Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research

CITATION

P. Clavert, J.C. Lutz, P. Adam, R. Wolfram-Gabel, P. Liverneaux, J.L. Kahn, Frohse's arcade is not the exclusive compression site of the radial nerve in its tunnel, Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research,

Volume 95, Issue 2, 2009, Pages 114-118, ISSN 1877-0568, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2008.11.001. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877056809000152)

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Abstract: Summary

Introduction

The radial tunnel is a musculo-aponeurotic furrow which extends from the lateral epicondyle of humerus to the distal edge of the supinator muscle. The superficial head of the supinator muscle forms a fibrous arch, the arcade of Frohse (AF), which is the most common site of compression of the radial nerve motor branch. The latter is less commonly compressed by the adjacent muscular structures. This tunnel syndrome might be worsened with repeated pronation and supination of the forearm. The double object of that work was: (1) to define the radial nerve anatomic landmarks, (2) to determine the anatomical relationship of the radial nerve main trunk and branches to the peripheral osseous and muscular structures in the anterior aspect of the elbow joint in order to identify which of these conflicting elements are likely to cause a compressive neuropathy.

Material and methods

The study design involved the dissection of 30 embalmed cadaveric upper limbs. Anatomic and morphometric investigations of the radial nerve, its terminal and motor branches were carried out. The presence of adhesions between radial nerve and joint capsule, tendons and aponeurotic expansions of epicondylar muscles and supinator arch was investigated. All measurements were taken in both pronation and supination of the forearm.

Results

Neither macroscopic radial compressive neuropathy at the level of the supinator arch nor adhesions between the radial nerve and the joint capsule were found. In four cases (13%), dense fibrous tissue surrounded the radial nerve supply to extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). The fibrous arch of the supinator muscle arose in a semi-circular manner and was noted to be tendinous in 87% of the extremities and of membranous consistency in the remaining 13%. The length of the AF averaged 25.9mm. The angle formed by the radial shaft and the supinator arch was 23°. Neither fibrous structures nor adhesions of the deep branch of the radial nerve (DBRN) along its course through the supinator muscle were observed.

Discussion

Anatomic studies have revealed a variable rate of occurrence of a tendinous AF, which range from 30 to 80% (87% in our study) according to authors. It is reported to be a predisposing factor to the development of chronic entrapment neuropathy of the DBRN, especially if it is thick and provides a narrow opening for passage of the DBRN. The tendinous consistency of the supinator arch is believed to develop in adults, in response to repeated rotary movements of the forearm. Repetitive pronation and supination of the forearm induces compression of the radial nerve and its branches between two inextensible structures. The fibrous AF and the proximal end of the radius (radial head and radial tubercle). This condition is aggravated by the supinator muscle repeated activity. Repetitive compression might then promote histological changes in radial tunnel content and progressive development of a local fibrous zone. We also observed that the radial nerve supply to ECRB could be entrapped between the superolateral aspect of the ECRB and the superior edge of the supinator muscle.

Keywords: Radial tunnel syndrome; Nerve entrapment syndrome; Paralysis; Anatomy; Lateral elbow tendinosis; Epicondylitis; Posterior interosseous nerve

Disclaimer:

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Produced by Jason Hooper (PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS) and Emile Modesitt

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial