Deload Weeks: Progression Hack or Harmful Crutch?

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 137

Introduction

Deload phases are touted by coaches and fitness influencers as an essential tool for avoiding injuries, breaking plateaus, and increasing physical performance long-term. Some even go so far as to claim that “if you don’t need deloads, you’re not training hard enough.” But here’s the problem: the research to back up deloads is virtually non-existent. And the logic that’s used to justify them is sometimes seriously flawed. In fact, other experts argue that if you do need deloads, it’s a sign of poor training. So… WTF? Are deloads the key to safe progression or a bandaid fix for bad programming? In this video, we get answers, and you become the most deload-savvy climber in the gym.

Defining Deloads

So what are deloads? They’re just short periods of reduced training, usually lasting a week. This means reducing the volume and/or intensity of your climbing, strength training, or both. Contrary to what some might think, most deloads do not involve a full cessation of activity. In fact, we actually *should* keep climbing and training during most deload phases, but we’ll talk about that later.

One thing to note is the difference between a deload and a “taper.” While the terms are often used interchangeably, tapers generally involve reduced training before a competition or high-performance phase. They’re usually a more gradual reduction in training and are carefully timed so the athlete is in peak shape for the substantial fatigue they’re about to encounter.

Deloads, on the other hand, are typically done either proactively or reactively during the training season. Proactive deloads are scheduled ahead of time at regular intervals. These are often programmed every 4-12 weeks, which often lines up well with people’s training cycles. In contrast, reactive deloads are mostly autoregulated, performed only when the athlete is feeling fatigued or performance has noticeably dipped.

Pretty simple, right? So where did this notion of a full deload week come from if we could just… take a rest day here and there?

The Theory Behind Deloads

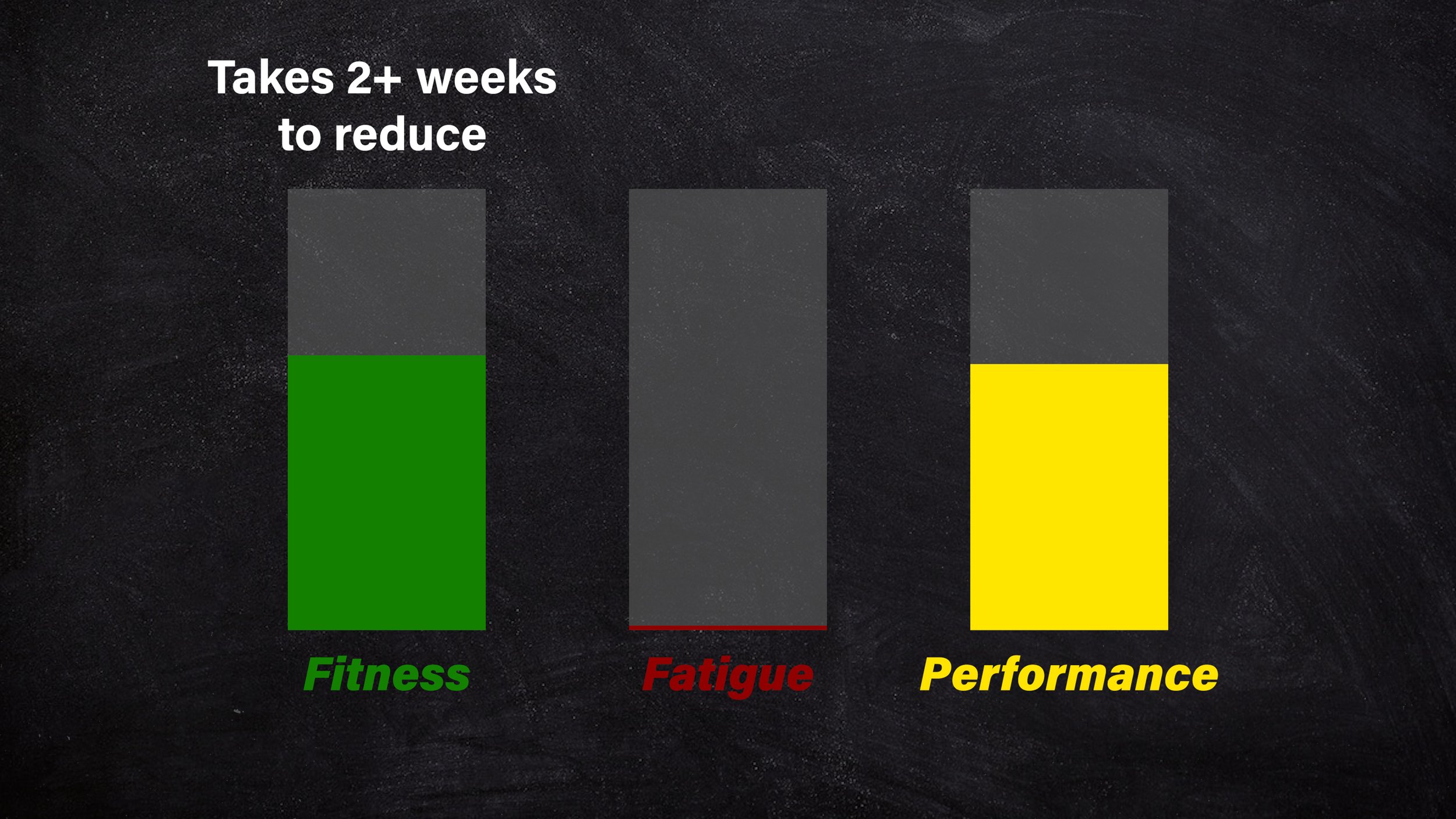

The concept behind deloads can be neatly illustrated with something called the “fitness-fatigue model.”

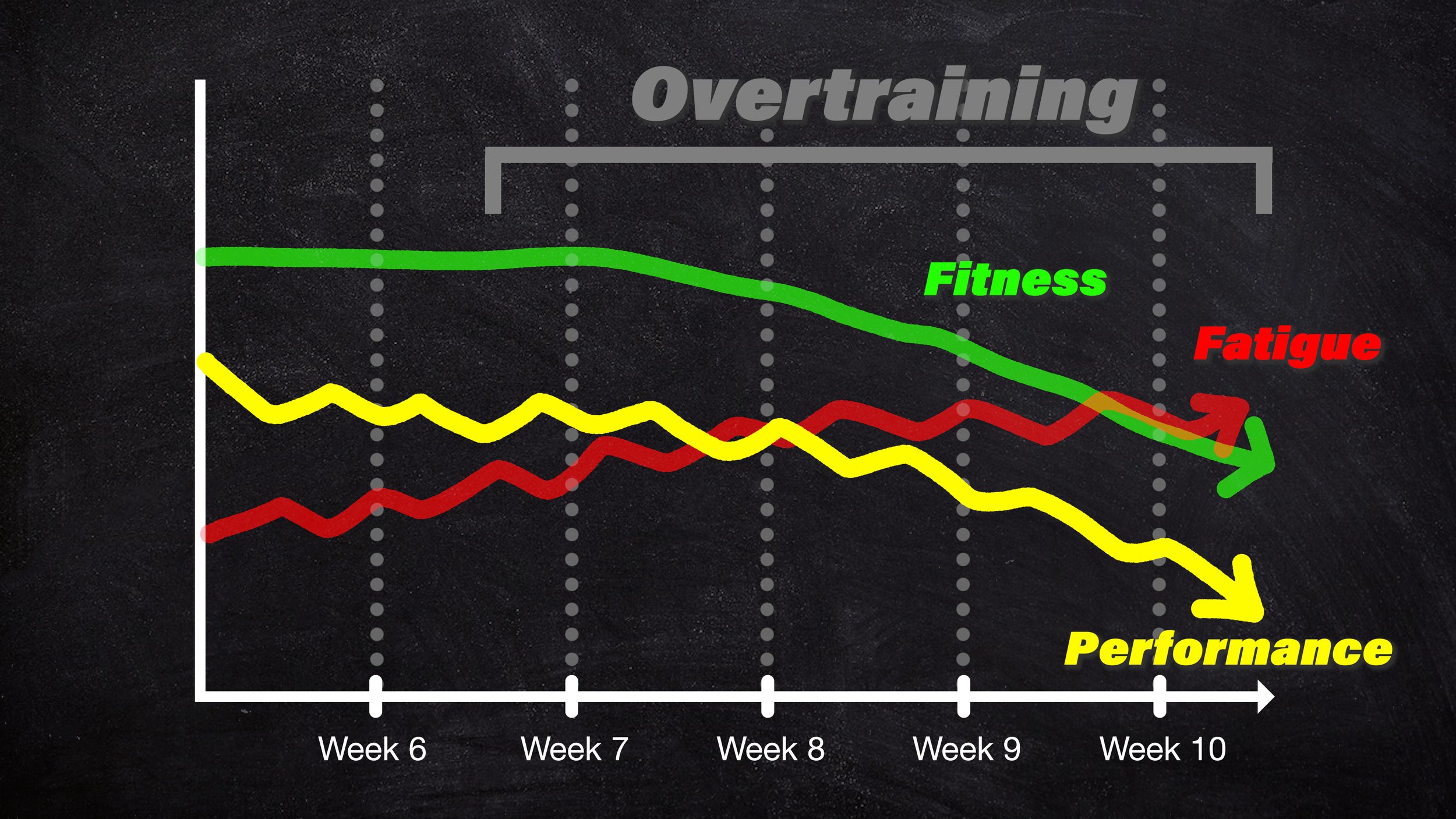

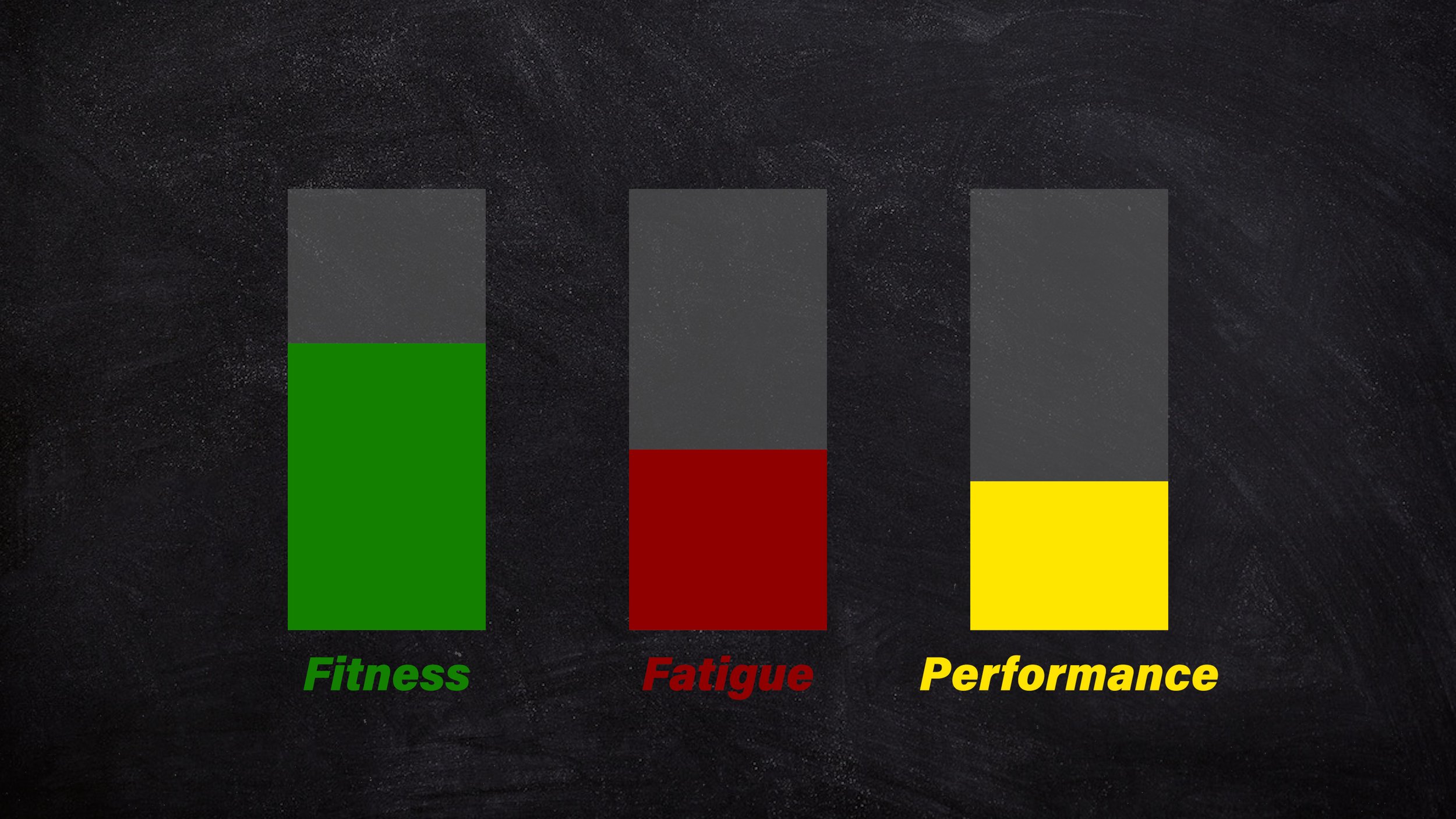

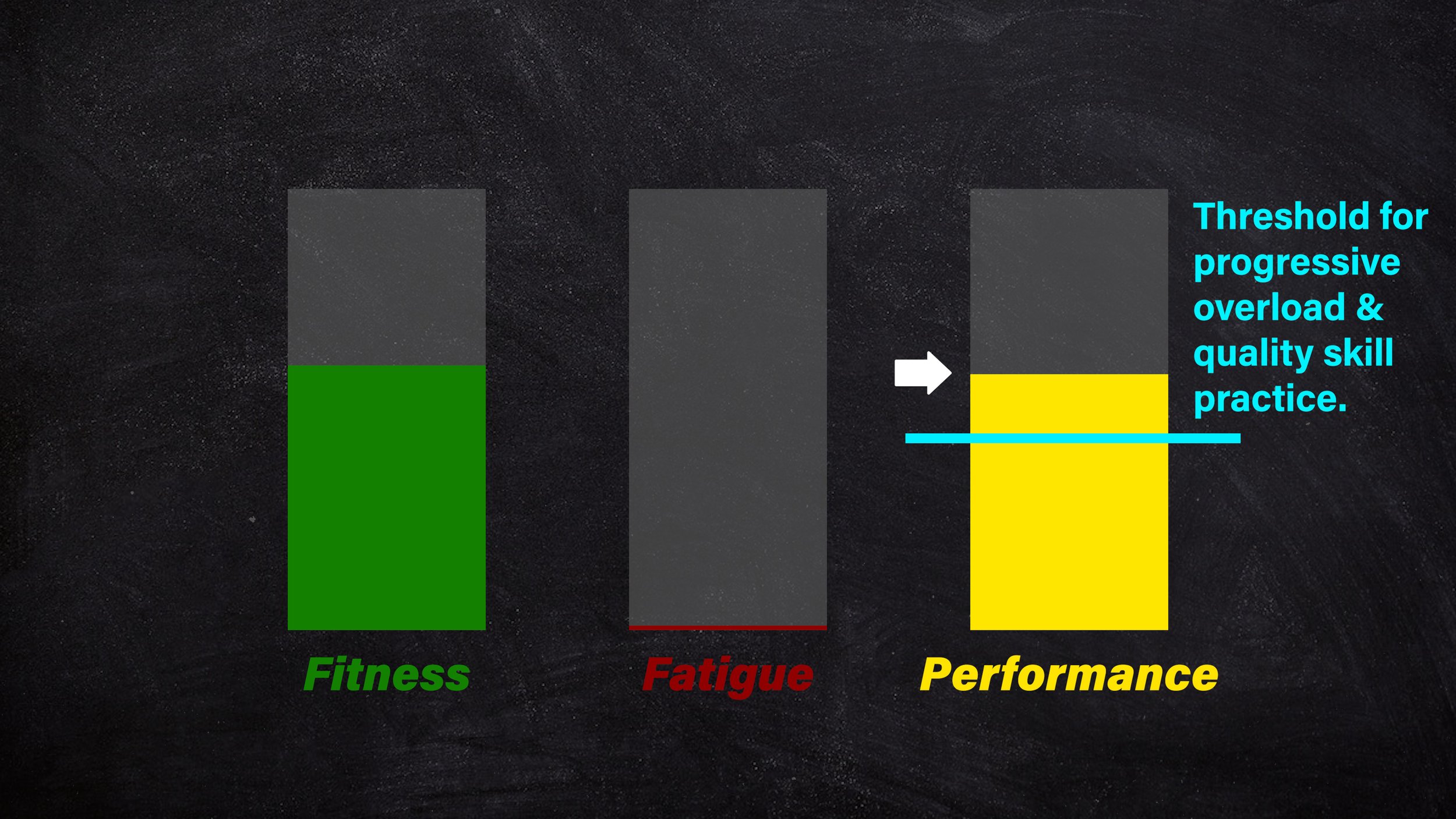

The model shows that our athletic performance or “preparedness,” at any one time, is a function of both our level of fitness and our level of fatigue. When we train to promote fitness adaptations, we incur some acute fatigue. When we rest, the fatigue dissipates. If we rest too long, we also lose fitness, but since that happens much more slowly, we can almost always recover before detraining occurs. So, as long as our fatigue is low enough by the time the next session rolls around, our *performance* will be high enough to once again achieve progressive overload and *quality* technique practice. This cycle makes it possible for us to consistently increase our fitness and performance over time.

However, we may not be able to maintain this every single week. With lots of climbing or hard training, it’s possible for mental and physical fatigue to slowly accumulate between sessions. Eventually, if our performance becomes too compromised for progressive overload and skill learning, we can no longer stimulate the adaptations we’re looking for. If we *maintain* this fatigue for too long or continue to accumulate more, we run the risk of what we call “overtraining.” This results in us “spinning our wheels” in the gym, stuck on the same problems for ages, feeling burned out, getting “tweaky” joints, or even suffering a more serious injury.

To stop all that from happening, we need a recovery method that drastically reduces fatigue. But we also want to lose as little fitness as possible. Enter: deloads! By strategically reducing our training load for a short period, we can then return to climbing at a higher level of performance than ever before. As long as we deload *before* we’re neck-deep into overtraining, one week appears to be plenty of time to accomplish this.

Now, none of this is particularly controversial. Everyone knows that if we train too hard for too many days in a row, we get tired and need more time to recover. But that does leave us with a bit of an unanswered question: what if we just… don't overtrain? Like, if we’re building up a bunch of fatigue between sessions and need to deload, wouldn’t that just mean we have a bad training program or subpar recovery? In some cases, yes.

The Argument Against Deloads

The main argument against deloads results from a few important science-based considerations.

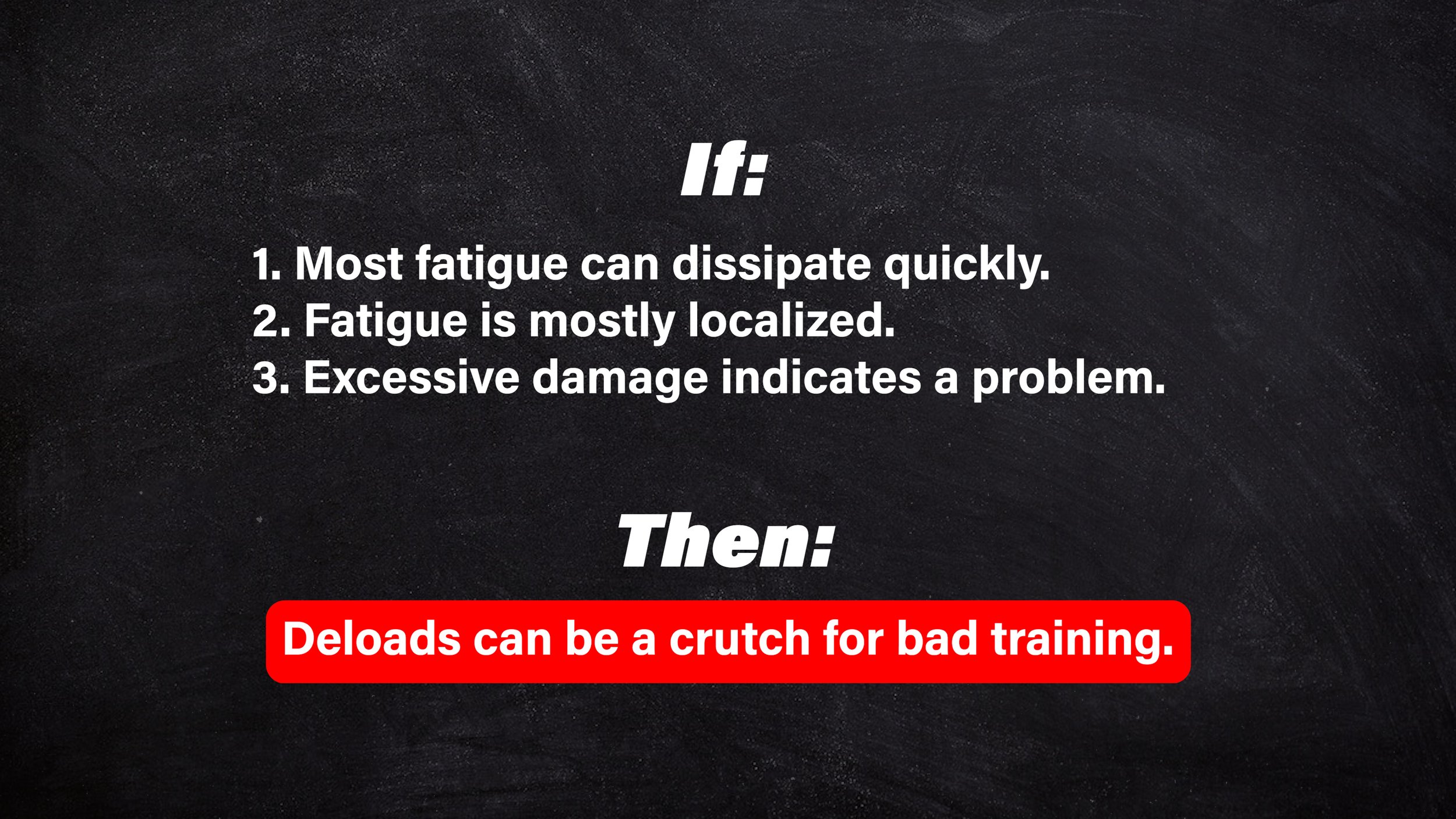

First, if we look at research on strength training, it appears most types of fatigue from a normal workout can resolve within a matter of hours, if not a day or two, depending on the intensity. This makes the idea of “inevitable fatigue accumulation” sound a bit dubious. If most or even all aspects of peripheral and central fatigue appear to dissipate quickly, it seems we *can* get stronger without incurring long-lasting fatigue.

Second, the most significant forms of fatigue seem to occur locally at the muscle. So, even if we do experience a bit of extra fatigue from, say, a back workout, that doesn’t mean our whole body is now equally fatigued and incapable of fitness adaptations in other areas. Why do we need a full deload when it’s just one part of our body that’s fatigued?

And third, if we *do* experience prolonged fatigue, it would most likely be from excessive muscle damage (which could also increase central fatigue) or possibly excessive connective tissue damage. But that would usually indicate we’ve gone way overboard on our workout or gotten some sort of injury. So… if we find we’re accumulating so much tissue damage that we basically can’t function without a deload every month, that’s clearly a problem. We either have compromised recovery capacity (due to poor diet, sleep habits, stress, illness, etc.) or we’re going way too hard. Either way, we’re putting ourselves at a higher risk of injury and burn-out while also losing valuable training time and practicing technique. So, using deloads to try to fix this can be seen as a bandaid for bad habits, poor programming, or less-than-ideal coaching.

Now, that’s by far the biggest con to the way deloads are sometimes used, but there are a couple other things to look out for.

For one, rigid deload protocols simply won’t work well for every athlete. Some may respond poorly to an abrupt interruption in training, especially if they’re making solid progress at the time. Plus, not all athletes will benefit from deloads at the same intervals, so using the exact same deload calendar for everyone is not ideal. Programming that fails to adapt to an athlete’s unique needs and preferences can be problematic.

And finally, the last issue with deloads is that they have no research to show they necessarily lead to better training outcomes. There is research on *tapers* which shows they are effective, but none of it shows what we really want to see: long-term comparisons between athletes that take deloads and athletes *cough climbers* that don’t. At the time of making this video, there is only one deload study remotely like this, but it’s not very helpful.

The study showed better strength performance results in the non-deload group than the deload group after the nine-week training intervention, but… 1) The deload group stopped all activity during the deload, which is not how most athletes use them. 2) There may have been a significant new-skill-learning aspect to the exercises they were performing, meaning the non-deload group had an extra week of practice. This is made more likely by the fact that muscle hypertrophy between groups was very similar. 3) The study had a limited population and study period of nine weeks, which isn’t much considering the skill-learning aspect may have prevented them from pushing their physical limits hard enough to accumulate fatigue.

In summary, I believe deloads are not a valid replacement for intuitive load management skills, self discipline, and good coaching, but that doesn’t mean I don’t recommend them. On the contrary…

The Argument for Deloads

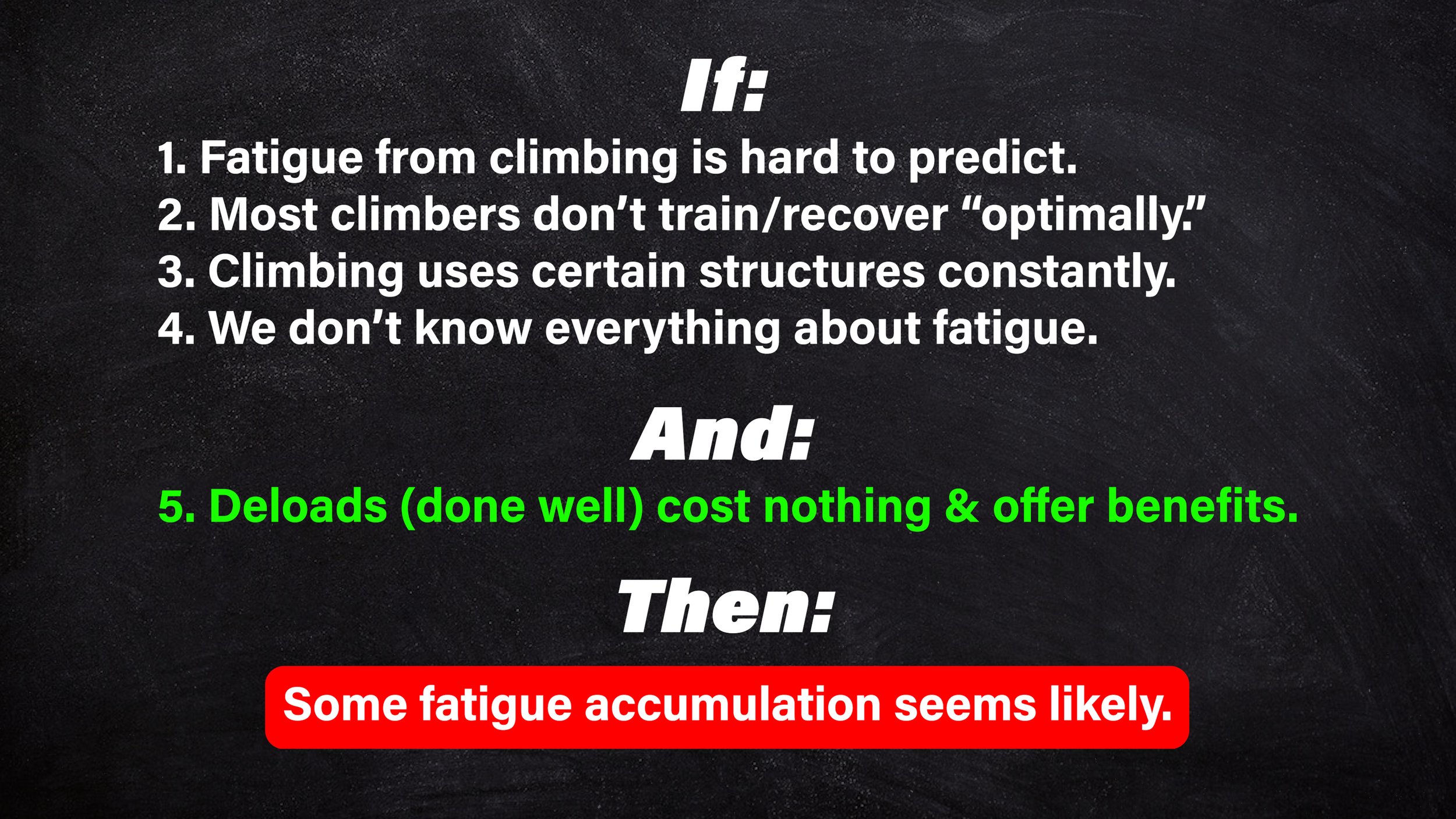

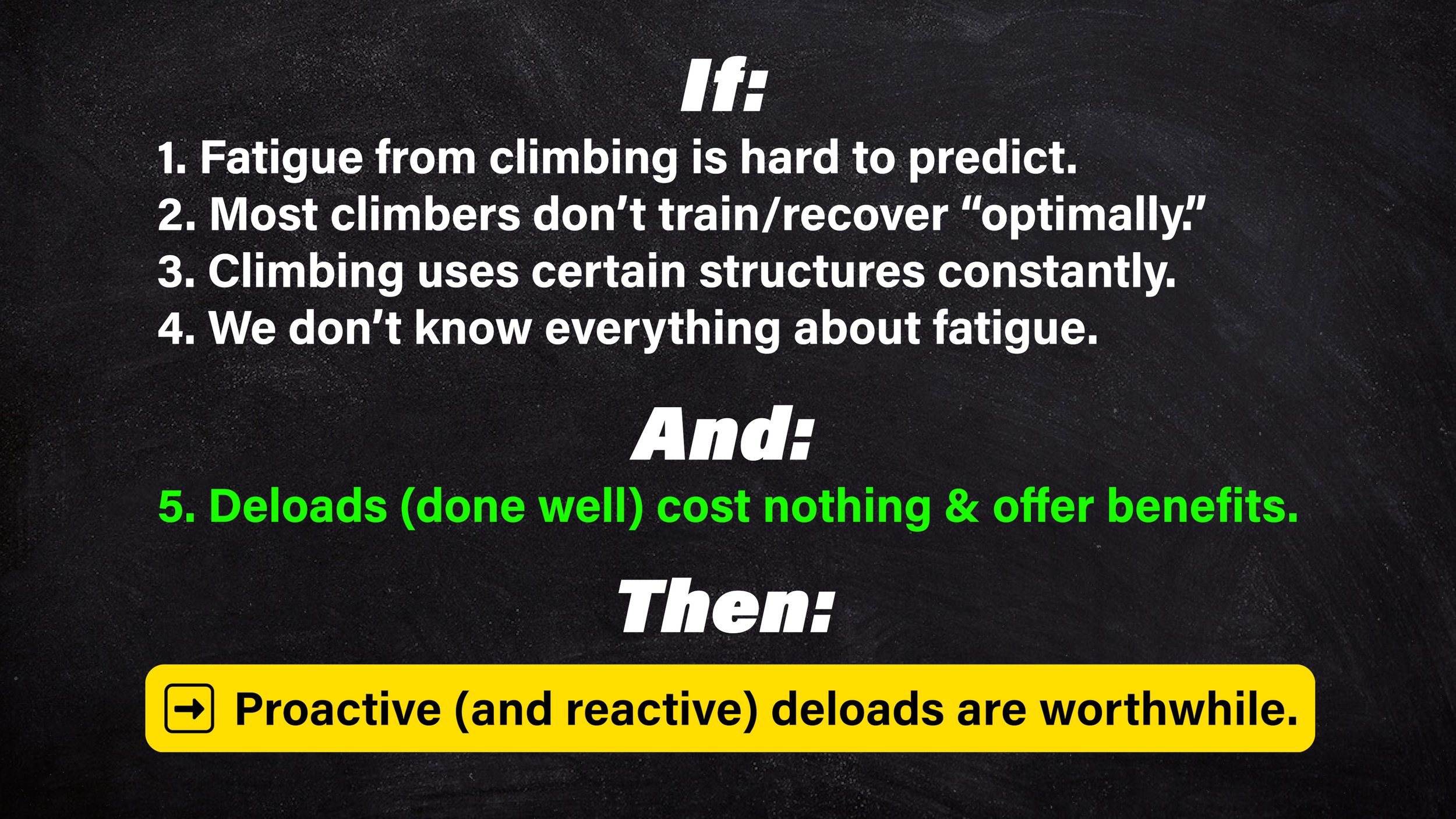

While I think it’s important to learn the science and theory behind all this stuff, it would be a mistake to lose sight of real-world practical experience. In fact, my main issue with the argument against deloads is that climbing can’t be quantified by science.

Climbing, like fatigue, is not just one thing, which makes “fatigue from climbing” impossible to define on a large scale. The fatigue we encounter from a day of trad climbing in the mountains will not be the same as a three-hour bouldering session in the gym. Fatigue from climbing will not be the same as strength training for climbing. Fatigue from crimps will not be the same as slopers. Starts to sound pretty complicated, right?

Now add the fact that most climbers are not following an ideal training program with optimized recovery habits. Not everyone has the resources to maximize fitness and minimize fatigue, and sometimes the allure of long sessions outweighs optimal training decisions. So, most climbers are susceptible to overdoing it.

Now add on top of *that* the fact that climbers tax some very specific tissues and joints every single session. While a bodybuilder can switch to training lower body when their upper body is fatigued, or train biceps when their lats are tired, a climber is usually using the same muscles and connective tissues on the wall. The fairly *relentless* use of these structures means we’re again more likely to build fatigue in those areas, and that’s probably why we see such a high prevalence of chronic climbing injuries. To make matters worse, many connective tissues aren’t good at giving us fatigue feedback, so we can’t always feel an impending injury.

And finally, we have to accept the limitations of our own knowledge. Exercise science simply doesn't know everything there is to know about fatigue. Maybe there’s an important type we’re overlooking? Did you notice we haven’t even mentioned mental fatigue? Which is of course important

When you add all those things up, predicting fatigue for climbing in general becomes impossible, though some fatigue accumulation sounds quite plausible in the real world. Therefore, I think the only logical conclusion is that proactive deloads are worthwhile for most climbers

Now that you know the pro’s and con’s, let’s talk about how and when to actually do them.

How to do Reactive Deloads

There is no science to tell us the optimal way to deload, but there are some useful guidelines to follow. Reactive deloads can be employed when you sense a noticeable drop in performance or increase in fatigue (mental or physical). It’s better to spot this early and it’s a lot easier to do so if you track your training, so we recommend all climbers keep a log. (Hint hint: If you want to support this channel and get $10 off my favorite finger strength tracking device, check out the Tindeq with the link in the description!)

If you’re deloading as a precaution or because you feel a little fatigue creeping up, a one-week reduction in volume (but not intensity) is my recommendation for both climbing and strength-training. Reducing volume means you will not encounter nearly as much fatigue as you normally would. But, maintaining intensity means you’ll still be able to get high-quality, near-limit skill practice and *maybe* slightly better retention of neuromuscular efficiency. The exact amount you reduce the volume depends on the climber and situation, but about a 25% reduction is a good place to start. Try it out, see how you respond, and adjust accordingly. If instead you don’t want to get that fancy, it’s perfectly fine to reduce volume, intensity, or both, in whatever manner you want -- as long as you’re doing less work in total.

If you’re deloading because you’ve got some aches and pains or more significant fatigue accumulation, I recommend a one week reduction in both volume and intensity of about 50%, particularly with any activities that load the affected area. So if it’s just your fingers that feel tweaky but the rest of you feels fine, it’s okay to maintain exercises that don’t tax your fingers. However, if you’re just feeling generally run down, you should reduce all training activities during the deload.

Finally, if you’re deloading because you’re experiencing prolonged muscle soreness, achy joints, chronic tiredness, mood swings, disrupted sleep patterns, or frequent injuries, you should check yourself. Issues this significant almost never happen overnight, nor do they come without warning signs in advance, so you may need to take an honest look at what lifestyle or training choices could lead you so astray. A deload is not a complete solution to a systemic overtraining issue. Nevertheless, if you are experiencing those issues, significantly reduced volume and intensity by 75-100% is certainly warranted to help your body get healthy again, possibly for two weeks or more. Also, as part of a solution to stop this from happening again, consider proactive deloads.

How to do Proactive Deloads

Proactive deloads can be performed in much the same way as reactive deloads, usually favoring a reduction in volume over intensity. The main difference will be how you add them into your training plan.

For beginners, proactive deloads are probably not necessary. You can do them if you’d like, but the low intensity at which newbie gains occur means regular old rest days will mostly be sufficient.

For more serious climbers who are pushing their bodies harder and maybe doing some supplemental strength training, I recommend deloads every 6-12 weeks. That’s a broad range, but remember climbers vary a lot. Twelve weeks is the longest I would personally go because some forms of fatigue are hard to sense. Conversely, anything less than six weeks is usually too frequent in my opinion, because at that point you’re losing a significant amount of training and skill practice every month. You can do it if you really want to as a preventative measure, especially if you’re just starting a new program and are unsure if you can handle the load. *But* if you find you consistently *need* a deload every three or four weeks, you should strongly reconsider your training or recovery habits.

For competition climbers, I recommend deloads in accordance with your coach’s training plan, or every 6-12 weeks, but even more so I’d suggest using tapers prior to competitions. Countless studies show increases in performance after one- to three-week tapers, so we'll put some guidelines on screen and links to more info in the show notes. [2, 3, 4]

Three weeks before competition, perform a gentle overreach week increasing volume and intensity slightly.

Start your first taper week with a reduction in volume by 25%, but maintain intensity (>85% your normal max).

Do a second taper week with a 50% reduction in volume, but similar intensity as the previous week.

Crush your competition

For climbers who want to maximize sendage on an upcoming climbing trip, I highly recommend tapers. In the week before the trip, maintain climbing intensity up to about 85% of your normal max, but cut the volume down by 50%. Additionally, consider reducing or even eliminating supplemental strength training, especially more taxing exercises like weighted pull ups and deadlifts.

For athletes who see climbing as a side-hobby and regularly engage in other sports like powerlifting or bodybuilding, deloads may be even more warranted than usual. Bodybuilding in particular, being solely focused on maximizing muscle damage to encourage growth, means athletes are specifically seeking out the longest lasting form of fatigue. This makes fatigue accumulation far more likely, but I’m no expert in bodybuilding, so I’d recommend channels like Stronger by Science, Jeff Nippard, and Renaissance Periodization for more information.

Conclusion

If for some reason you’ve already forgotten everything we’ve said in this deload breakdown, here is a perfect summary from Dan Beall: [Clip of Dan from the Overrated video saying “I think not enough people do them, but the way they get talked about is a little too hype-train.”]

If you want to support more free content on this channel, please consider shopping with our affiliate links which will sometimes even get you discounts! Until next time: train, climb, send, take an occasional deload, and repeat.

CITATIONS

Imbach F, Sutton-Charani N, Montmain J, Candau R, Perrey S. The Use of Fitness-Fatigue Models for Sport Performance Modelling: Conceptual Issues and Contributions from Machine-Learning. Sports Med Open. 2022;8(1):29. Published 2022 Mar 3. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00426-x [1]

Bazyler CD, Mizuguchi S, Harrison AP, et al. Changes in Muscle Architecture, Explosive Ability, and Track and Field Throwing Performance Throughout a Competitive Season and After a Taper. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(10):2785-2793. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001619 [2]

Wang Z, Wang YT, Gao W, Zhong Y. Effects of tapering on performance in endurance athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0282838. Published 2023 May 10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0282838 [3]

Travis SK, Mujika I, Gentles JA, Stone MH, Bazyler CD. Tapering and Peaking Maximal Strength for Powerlifting Performance: A Review. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(9):125. Published 2020 Sep 9. doi:10.3390/sports8090125 [4]

Carrard J, Rigort AC, Appenzeller-Herzog C, et al. Diagnosing Overtraining Syndrome: A Scoping Review. Sports Health. 2022;14(5):665-673. doi:10.1177/19417381211044739 [5]

Tornero-Aguilera JF, Jimenez-Morcillo J, Rubio-Zarapuz A, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Central and Peripheral Fatigue in Physical Exercise Explained: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3909. Published 2022 Mar 25. doi:10.3390/ijerph19073909 [6]

Refalo MC, Helms ER, Hamilton DL, Fyfe JJ. Influence of Resistance Training Proximity-to-Failure, Determined by Repetitions-in-Reserve, on Neuromuscular Fatigue in Resistance-Trained Males and Females. Sports Med Open. 2023;9(1):10. Published 2023 Feb 8. doi:10.1186/s40798-023-00554-y [7]

Jäkel B, Kedor C, Grabowski P, et al. Hand grip strength and fatigability: correlation with clinical parameters and diagnostic suitability in ME/CFS. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):159. Published 2021 Apr 19. doi:10.1186/s12967-021-02774-w [8]

DISCLAIMER

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com

IG: @emile166