Collateral Ligament Injury from Rock Climbing (Causes & Fix)

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 130

INTRODUCTION

There is so little information out there on this issue, so in this video, we’re going to cover the signs and symptoms of a collateral ligament injury, a test you can do to help identify what your injury actually is, common ways collateral ligament injuries occur, possible treatments, and perhaps most importantly of all, whether or not you can still climb during rehab.

ANATOMY

So what are these weird ligaments and what do they even do?

The collateral ligaments are fibrous bands of connective tissue that function to stabilize finger joints. In this case, we are going to discuss the PIP and DIP collateral ligaments specifically, since those will be most relevant to rock climbers. Their role is to stabilize and prevent excessive varus or valgus forces, aka, sideways or lateral bending of the joint. They originate more on the dorsal side (or back) of the proximal phalanx and run obliquely to the palmar side (or front) of the distal phalanx, which is important for understanding our symptoms later on.

CAUSES

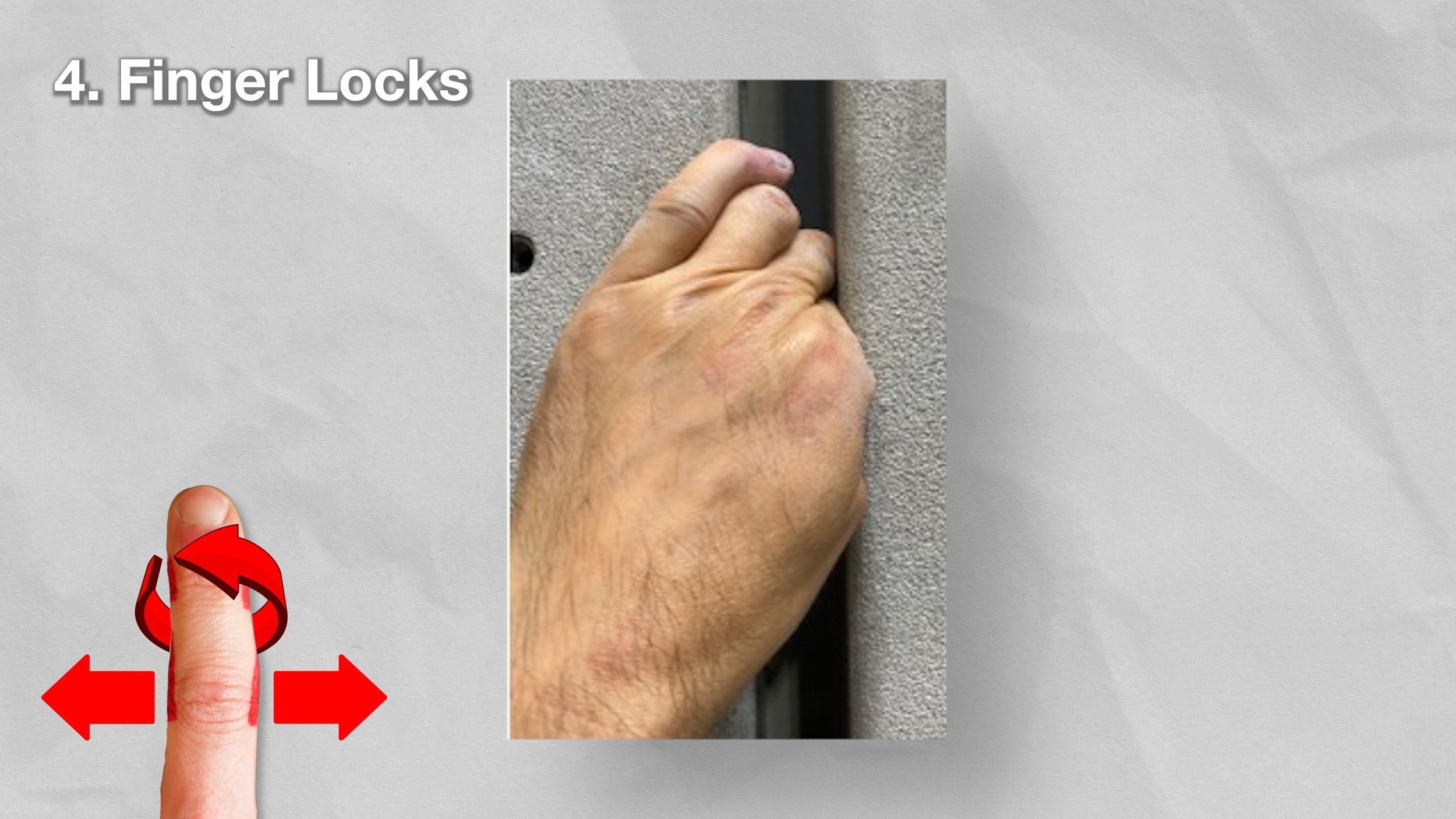

Now that we know the anatomy, we can more easily understand how this ligament can become injured while climbing, particularly with excessive sideways pulling forces. Here are a few clear examples of that:

Sidepulls, especially if you are underneath the hold, or moving dynamically up to a hold much further away while remaining on the sidepull.

Wide or far-reaching moves that cause you to ulnarly or radially deviate the wrist.

Gastons that are far overhead or significantly out to the side.

Fingerlocks, especially if heavily loaded due to poor feet or poor wrist positioning

You may have noticed a general trend with a few of those; this ligament is more likely to be strained when the wrist is not in line with the hold, meaning you have ulnar or radial deviation of the wrist.

Also, in general, injury to the collateral ligament is more likely with dynamic movements than static ones because you’re more likely to experience uncontrolled movement, higher acute forces, and/or less time for feedback from your body. But, it is still possible to suffer an injury when performing an intense static movement.

There are, of course, other causes of collateral ligament injuries, such as acute trauma. For example, a dislocation of the joint can result in damage to the collateral ligament and should be evaluated by a specialist to determine the need for further assessment or imaging.[1]

TESTING & DIAGNOSIS

If you suspect you’ve injured your collateral ligament, here are some common signs and symptoms. Make sure to only use mild to moderate pressure when testing yourself; you should never have to exert large amounts of force or endure more than mild discomfort, if any. Pressing hard enough anywhere in the body can produce pain, so be gentle.

Pain on one side of a single joint (DIP or PIP).

Tenderness to palpation here as well.

Possibly swelling, redness, and inflammation.

Loss of range of motion and/or pain reproduction with joint flexion.

Hypermobility or pain when performing a lateral stress test.

This last one is quite important, as it can help delineate between grades and severity of injuries.

It should be performed with the joint both in about 10 degrees and 30 degrees of extension to test both collateral ligaments.

If these symptoms apply to you, the next step would be determining the severity of your injury, which will help us make more informed rehab decisions. Unfortunately with collateral ligaments, determining the severity on your own can be pretty tricky. We’re still going to provide a little guide to help you, but if you are experiencing any instability with the lateral stress test, you should see a skilled professional for further evaluation.

A low-grade, or grade 1, injury may have swelling and tenderness specifically over the affected collateral ligament and may even produce discomfort with the lateral stress test, but there will not be instability with the test.

A moderate, or grade 2, injury will typically have increased swelling, perhaps in the entire joint now, and will produce instability with the lateral stress test. BUT, it will have an eventual firm endpoint and typically the amount of deviation is small, less than 20 degrees.

A severe, or grade 3, injury will of course be accompanied by swelling, but will now produce significant laxity with the lateral stress test. It will be greater than 20 degrees but still may still present with a firm end feel.[1]

Now, before we make a final determination and move on to treatment, we should do our best to rule out other possible causes of these symptoms besides a collateral ligament injury.

RULING OUT OTHER INJURIES

The most common injury we need to rule out, because of its similarity to collateral ligament injuries, is joint synovitis. Synovitis will present with similar symptoms, swelling, pain and/or limited joint range of motion, and pain with pressure over the joint. But, synovitis has a few clear differences.

With synovitis, there will be no instability with the lateral stress test, though mild pain may be provoked

Synovitis usually presents with more diffuse pain and can occur on both sides of the joint or even on top of the joint simultaneously. Compare that to a collateral ligament injury which is unilateral in nature (unless of course somehow you damaged both collateral ligaments on either side of the joint, which would likely only occur with a traumatic injury).

Swelling is typically greater with synovitis, and more chronic or progressive in nature, than a collateral ligament injury unless the collateral ligament injury is severe

Synovitis typically builds up over time as a chronic injury. Collateral ligament injuries may be more traumatic or may be related to multiple attempts at a single problem or style of climbing.

Synovitis typically presents with increased swelling on BOTH sides of the joint, rather than the single-sided swelling of a collateral ligament injury.

Joint synovitis and a collateral ligament injury can also coexist, so if you’re having trouble differentiating the two, you could have both issues or you may just need to seek out help from a professional for an accurate diagnosis. I recommend seeing a qualified PT or doctor with some knowledge of climbing if at all possible. You can make a virtual or in-person appointment with me through our website if you like: link in the description.

There are technically other injuries that could cause similar symptoms, like extensor hood injuries and avulsion fractures, but those are a bit less likely and require a professional to diagnose.

REHAB

As for rehab, let’s discuss some of the do’s and don’ts while treating this injury, as well as my recommendations for specific types of rehab activities.

Can I Still Climb?

First, everyone’s main question: “can I still climb with this injury?” The answer, of course, depends on the severity of it. If you believe you have a Grade 2 or Grade 3 injury, are experiencing significant instability in your finger, or are experiencing more than a 3/10 pain at baseline or with basic range of motion, you should probably wait until your symptoms improve or until you get clearance from a skilled professional. But if you have no instability and the pain is manageable, here are a few things to avoid, and things to do, while climbing.

Things to avoid:

Sidepulls that you can’t grab with a straight line of force

Wide or far-reaching holds

Dynamic movements to or from smaller holds (jugs are typically OK)

Fingerlocks / ringlocks

Generally, positions that create ulnar or radial wrist deviation while climbing. (This is typically what causes the lateral forces at the fingers, which may exacerbate your symptoms and potentially slow healing.)

Things to do:

Try to keep your wrist in line with the direction you’re pulling to avoid lateral forces on the fingers.

Reduce dynamic climbing. Load the fingers in a controlled manner and stop if the position causes you pain.

Use this as an opportunity to work on technique, including trying to take more stress off of the fingers by using your feet more effectively and finding balanced body positions. This is especially important while the fingers are loaded at non-linear angles.

Things to consider:

Taping could be used for support, simply to reinforce the joint and help reduce the stress of lateral forces while climbing. Or, you could consider buddy taping, to help further stabilize the joint and reduce unwanted forces.

Treatment

As for specific forms of treatment, unfortunately, with this injury, there isn’t a ton you can do other than waiting it out and not exacerbating it with climbing. Sadly, facepulls won’t save you in this situation 😡. But, there are a few things you can do.

Note: most of this is simply based on expert opinion. Research is limited on the best approach and decisions should ultimately be left up to the individual and their response.

Active Range of Motion

Maintaining healthy joint range of motion is important because it improves outcomes with these injuries by preventing adhesion formation and encouraging proper organization of the healing tissue, among other factors. [2]

We can use tendon gliding to achieve this. Simply think of the middle of your palm and the base of your knuckles as two lines, with the middle of the palm being easier (less joint flexion) than the base of the knuckles. Touch the fingertips to those lines, fully opening or extending your hand in between, and repeat. If this is painful, stop at or before the pain increases beyond a 2/10. If you can only touch the middle row without pain, that is fine for now, but progressively work on touching the knuckle row as well over time. This healthy motion can help lightly stimulate the collateral ligament without directly irritating it. Perform 6-10 repetitions, multiple times a day.

Exercise and BFR

It’s essential to stay active and keep the body, especially the upper extremities and hands, moving! This is a great time to introduce more gym training to your program while reducing your climbing. Consider introducing compound movements to your training to work on any weaknesses you’ve been neglecting. You can even perform safe finger strengthening if you have a lower-grade injury. Essentially, anything that does not cause pain at the finger is encouraged (except of course obvious exercises that put direct lateral forces on the fingers).

You could also consider implementing blood flow restriction training at this time to potentially increase the response of the tissue without as much load.

Manual Therapy

Gentle cross-friction massage techniques can be applied to this area to try and stimulate the tissue. Simply use your other hand and apply gentle pressure over the affected area, and move in small motions up and down, left and right. Perform for 2-3 minutes daily, or even up to 2-3 times a day.

Gentle Joint Mobilization

Gentle joint mobilization may be beneficial for a grade I injury. Simply grab your finger just in front of the injured joint, while the joint is in a neutral or straight position. Then, pull gently straight away from the joint. This gentle mobilization can be helpful for the joint itself, but also can apply a gentle load to the ligament which, if done appropriately, may assist with healing. Recall with our testing section, we don’t want to create a lot of pain with this, so only pull gently.

If you have a Grade 2 or Grade 3, or you have generalized laxity or instability, refrain from performing this treatment. Otherwise, perform this up to twice daily until your symptoms resolve, or if you are limited in your range of motion, perform this in conjunction with your active range of motion and then stop when your range has normalized.

Rice Bucket Exercises?

This may be a rare case where rice bucket work *could* help. The gentle lateral load might be appropriate for a less severe (grade 1) injury, as it could stimulate the tissue without irritating it. I still wouldn’t say that it’s worth buying a rice bucket just for this, but if you already have access to one, see how your finger feels with it with a few gentle motions. If it feels better, great! If not, discontinue and stick to the basics.

Ice and Heat?

In the acute phase of an injury (the first few days), or when experiencing excess swelling or discomfort, ice would be appropriate. If you do not meet those criteria, I would personally withhold icing unless you just really love it and have found great results in the past. In general, we don’t need to stop the inflammatory process as long as it’s not becoming excessive.

Heat may help to improve your range of motion and may improve blood flow to the area, but there’s no reason to think that this guarantees the blood will then be directed into your healing collateral ligament.

I have never personally been a huge fan of ice or heat, but since there are not a whole lot of specific treatments for this injury and ice and heat present little to no risk, it might be worth trying out for yourself to see if it helps!

Patience

The most important exercise: patience. This is a piece of connective tissue so it will take time, and there is no magic bullet to speed up the process. But, like any injury, sleep, hydration, nutrition, and stress levels can all play a big role in your recovery timeline.

Surgery

Surgery is only advisable for grade 3 injuries. Conservative care (and patience) should be the first line of management in most cases.

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis for a Grade I injury is fantastic. As long as you reduce aggravating factors and are patient, you will have no problem returning to full prior level. It may still take 8-12 weeks to feel back to normal, though, as this tissue can be slow to heal.

If you have a Grade II injury, prognosis remains great, but you need to be more patient and may need to work with a skilled therapist to work on additional stability. It may take 12-16 weeks to feel most of your strength returning.

If you have a Grade III injury and are having issues with your daily functions, surgery may be required but once again prognosis is good if you receive proper rehab after.

CONCLUSION

If you’re still unsure about your injury or feel like you want a more personalized treatment plan, be sure to reach out to a skilled professional, ideally with some knowledge of climbing. If you want, you can schedule an appointment with me using the link in the description. Until next time: train, climb, send, repeat!

RESEARCH

Kamnerdnakta S, Huetteman HE, Chung KC. Complications of Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Injuries: Prevention and Treatment. Hand Clin. 2018;34(2):267-288. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2017.12.014

Rozmaryn LM. The Collateral Ligament of the Digits of the Hand: Anatomy, Physiology, Biomechanics, Injury, and Treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(11):904-915. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.08.024

Carruthers KH, Skie M, Jain M. Jam Injuries of the Finger: Diagnosis and Management of Injuries to the Interphalangeal Joints Across Multiple Sports and Levels of Experience. Sports Health. 2016;8(5):469-478. doi:10.1177/1941738116658643

DISCLAIMER

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com

IG: @emile166